In the previous classes we have seen the rise of what is called”feudalism”, rise of “clan monarchies” (term used by UN Ghoshal – Contributions to the History of the Hindu Revenue System, 1929), i.e., Gurjara-Pratiharas, Gahadwalas, Chahamanas, Palas, Senas, Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas etc. We have also seen the developments and churnings in philosophical thoughts – Shankara, Ramanuja, and the rise of “Bhakti”.

Let us now deal briefly with some other developments of this period: society, technology, science, and literature. In the end we will also go through the developments in the field of Art and architecture.

Works of Simon Digby (War Horses & Elephants), as well as a series of papers by Irfan Habib on technology have shown that one of the direct results of all this, especially setting in of feudalism, was that by 7th C, cavalry started emerging: it became quite important. We will come to this in some details later. But along with this, the period saw the emergence of a new social category, the horsemen, the rajaputras. Their emergence was facilitated not only by the land grants, the tamapatras etc, but also due to the coming of a new technology.

One of the first source of information for this development is the Chachnama, the chronicle detailing the conquest of Sind. When the Sind ruler, Dahar, was defeated by the Arabs in 712-13 AD. It mentions that Dahar was surrounded by 5000 ‘ibnul muluk’, son of kings – a direct translation of the term rajaputra of Sanskrit. Another term used for them is rauta (Prakrit) and they were mounted lancers.

They bonded together to carve territories which were semi-independent. They held villages / territories which were hereditary possessions.

The Lekhapadhiti Documents (9th-13th C Gujarat) as well as Arabic and Persian texts from 8th C onwards mention Samantas, thakkuras, ranakas, nayakas, etc as those who were hereditary class of potentates above them. Similarly mentioned are khuts, muqaddams, and chauduries. The raja / raya (kings) were mere heads of a confederacy of such chieftains.

Similarly in the South, as per the researches of Burton Stein (Peasant State and Society in Medieval South India) “segmentary states’ gave rise due to a primitive peasant society marked by a 2-varna system of Brahmins and Shudras. There were no kshatriyas or Vaishya class there.

During this period, the caste system too became very rigid. This is gleaned from a number of primary sources like Rajataringini of Kalhana, Chachnama (13th C Persian tr. Of the account by Ali Kufi) and Alberuni (esp. Kitab ma’al Hind). It appears that a Brahman dynasty was established in Sind. And it suppressed the pastoral communities like Jatts, by imposing rules from Manusmriti.

Alberuni mentions the rigid caste system and mentions 8 antajya communities who were outcastes, living outside towns and villages. Basing strictly on Smritis, he places weavers amongst antajyas. A contrary information however, comes from Pancatantra: weavers were shown as Vaisyas.

Harsher rules were imposed on woment – and there is mention of sati.

According to AS Altekar (Position of Women in Hindu Civilization, 1956) the first ritual widow burning is reported from 316 BC when a widow of an Indian captain was burnt in Iran. Bana Bhatta criticizes this practice in 7th C AD. But by 11th C it appears to be quite widespread amongst women of rulers, nobles & warriors.

From Lekhapadhiti Docs, we come to know of women sold in slavery. And when so sold, they lost their caste status, as well as family ties. They were made to do all types of work, both in house and fields and were in constant threat of violence and torture.

However, from Kalhana (1151) we come to know of Jayawanti, a dancer, who kept changing partners, and ultimately ended up as a queen of the king of Uchcha in Kashmir (1101-11) and became famous for her benevolence and wisdom. We also have a sculpture of a woman from Khajoraho (10-11th C) with a slate and a pen: education, writing and wisdom.

By 11th C, Kaivartas, an outcaste jati in Manusmriti (1st C BC) rose in rebellion under the Palas and gained recognition as a clean caste under Ballalasena of Bengal (1159-85). [RD Banerji, The Palas of Bengal, 1973]

Similarly Jatts who were considered out castes, gathered enough power in 11th C to fight Sultan Mahmud (998-1030). They were now considered Sudras. [Irfan Habib, “Jatts of Punjab & Sind”, Essays in Honour of Ganda Singh, ed. H Singh & NG Barrier, 1976).

Technological Developments, 700 -1200

The period was earlier thought to be a stagnant period – not only as far as economy was concerned – with land-yield falling (DD Kosambi), or at most static (Burton Stein, S India). Recent works however have shown that the period, contrary to these pessimistic projections, was a period of some progress, at least in the field of technology.

One area where development is encountered is the field of irrigation technology, which must have led to some improvement in the cultivation of crops and yields.

Between c.600 – 1500, tank irrigation started in a big way. Remains of at least two great reservoirs survive: one from 11th C, the reservoir of Raja Bhoja; and the other from 15th C, a reservoir at Madang in Karnataka. At Karnataka, one of the earthen embankments was 240 m thick, 30 m high, and designed to fill a lake 16-24 Km long. According to the Gazetteer of Bombay Presidency, it had gigantic sluices.

Water was drawn using leathern buckets tied to a rope over pulley wheel. There is a mention of noria or arghatta (pot on wheels). By 6th C, a mala (potgarland) was added. Epigraphic evidences, plus references in Bana’s Harsha Charita.

We also have the Mandor Frieze (12th C) where manual labour is shown turning the wheel. The frieze also depicts a cart drawn by camels.

The rotary handmills make an appearance during 5th C : Kunal monastery, Tazila.

Lallanji Gopal in an article [‘Technique of Agriculture in Early Medieval India, c700 – 1200 AD] published in an Allahabad University journal in 1963-64, mentions literary references to bullocks used in threshing (bullocks going round and round) – in dictionaries Abhi dhāna ratnamala (c.950) and Vijayanti (11th C) etc

In crafts, we find the introduction of two devices:

1) Indian Cotton gin for separating seed from fibre: rollers. We have it is a fresco from Ajanta. It does not have a crank handle

2) Bow scutch for separating fibres: Jatakas & Milindapanho (early C AD)

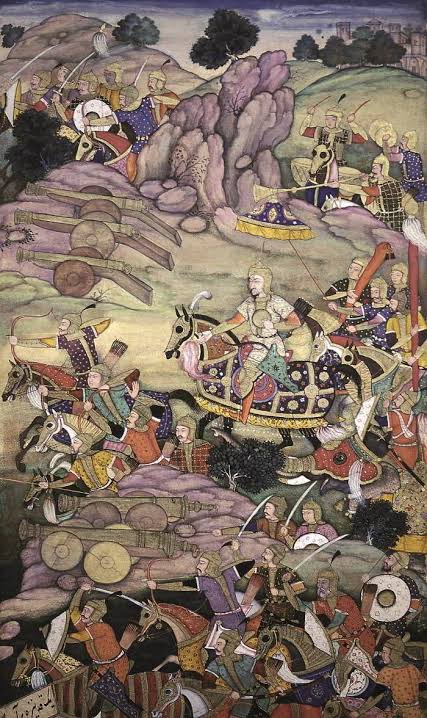

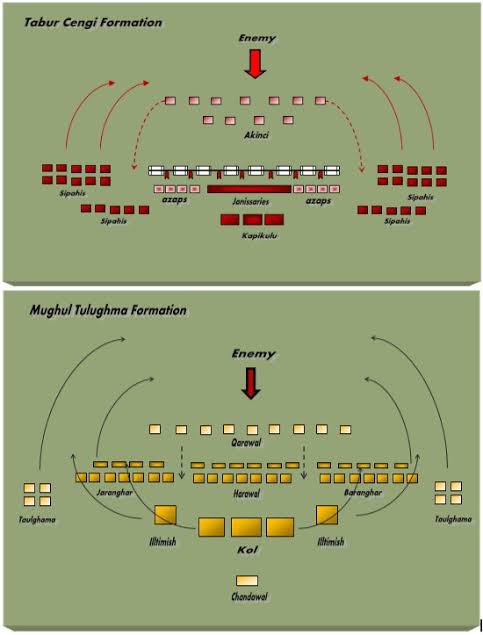

Military Technology

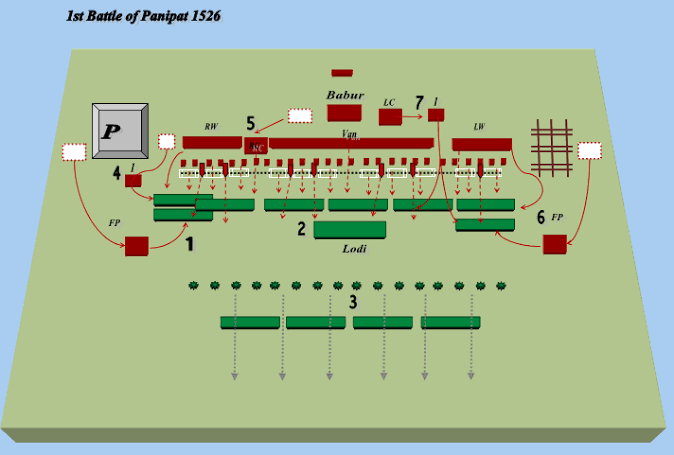

By 7th C the horse drawn chariots as prominent vehicles of war decline and disappear. Now emphasis is much more on Cavalry horsemen.

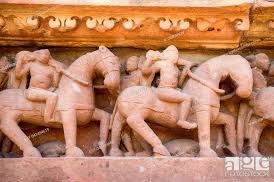

Saddles took time to appear. Stray ref is found in Khajoraho sculpture

Iron stirrup too is not encountered

A broad wooden stirrup at Khajoraho (10th C) and possibly a leather (?) ring stirrup at Konarak (c 1250).

No iron shoe as well. However one isolated eg from Hoysala sculpture at Karnataka

Catapult too was probably not known. First use encountered by the invading Arabs who came in 712-14 to Sind: Greek Fire (naphtha) & mangonels (manjaniq)

Sciences

In mathematical sciences, Bhaskar II (b. 1114) wrote Lilavati (arithmetic) & Bijaganita (algebra)

During 6th C Varahamihra wrote Pancasidhhantika and Brihatsamhita

By 628 AD Brahmagupta wrote Brahmasphuta Siddhant which was an astronomical and mathematical treatise.

Alberuni:

Alberuni appears to appreciate the Indians for their knowledge of the sciences. For example at one place he exclaims: ‘The Greeks, though impure, must be honoured, since they were trained in sciences, and therein excelled others. What, then, are we to say of a Brahman, if he combines with his purity the height of science?’

On arithmetic Alberuni observed that the Indians do not use the letters of their alphabet for numerical notation, as against the Muslims who use the Arabic letters in the order of the Hebrew alphabet. The use of Arabic letters for numerals must not have been in wide use when Alberuni wrote in AD c.1030, for these have been communicated to the Arabs in the eighth and ninth centuries a fact which he goes on to accept that ‘the numeral signs which we use have been derived from the finest forms of Hindu signs’. Having observed the names of the orders of the numbers in various languages he had come in contact with, Alberuni found that no nation goes beyond the thousand, including the Arabs. Those who go beyond the thousand in their numeral system are the Indians who extend the names of the orders of numbers until the 18th order.

Pulisa has adopted the relation between the circumference and diameter of a circle to be 177/1250 which comes out to 3.1416. While ancient Puranic traditions about Earth and the heavens and their creation still existed, these were in direct opposition to the scientific truths known to Indian astronomers. While it is not possible to mention all the theories and concepts prevalent at the time, let it suffice to say what some of the ideas of Hindu astronomers that Alberuni found interesting were. Quoting Brahamgupta, Alberuni wrote:

“Several circumstances, however, compel us to attribute globular shape to both the earth and the heaven, viz. the fact that the stars rise and set in different places at different times, so that, e.g. a man in Yamakoti observes one identical start rising above the western horizon, whilst a man in Rum at the same time observes it rising above the eastern horizon. Another argument to the same effect is this, that a man on Meru observes one identical star above the horizon in the zenith of Lanka, the country of demons, whilst a man in Lanka at the same time observes it above his head. Besides all astronomical observations are not correct unless we assume the globular shape of heaven and earth. Therefore we must declare that heaven is a globe, and the observation of these characteristics of the world would not be correct unless in reality it were a globe. Now it is evident that all other theories about the world are futile.”

Quoting Varahmira, he further continues:

“Mountains, seas, rivers, trees, cities, men, and angels, all are around the globe of the earth. And if Yamakoti and Rum are opposite to each other, one could not say that the one is low in relation to the other, since low does not exist…. Every one speaks of himself, ‘I am above and the others are below,’ whilst all of them are around the globe like the blossoms springing on the branches of a Kadamba-tree. They encircle it on all the sides, but each individual blossom has the same position as the other, neither one hanging downward nor then other standing upright.”

He further emphasized: ‘For the earth attracts that which is upon her, for it is the below towards all directions, and heaven is the above towards all directions.’

There was no consensus about the resting or movement of the earth. Aryabhatathought that the earth is moving and the heaven resting. Many astronomers contested this saying were it so, stones and trees would fall from earth. But Brahamgupta did not agree with them saying that that would not happen apparently because he thought all heavy things are attracted towards the center of the earth.

On the topic of ocean tides, Alberuni wrote that the educated Hindus determine the daily phases of the tides by the rising and setting of the moon, the monthly phases by the increase and waning of the moon; but the physical cause of the both phenomenon is not understood by them.

The Hindus have cultivated numerous branches of science and have boundless literature, which with his knowledge, he could comprehend. He wished he could have translated the Panchatantra, which in Arabia was known as the book of Kalila and Dimna.

Hindu laws, Alberuni observed are derived from their rishis, the pillars of their religion and not from the prophets, i.e. Narayana.

“Narayana only comes into this world in the form of human figure to set the world right when things have gone wrong. Hindus can easily abrogate their laws for they believe such changes are necessitated by the change of nature of man. Many things which are now forbidden were allowed before.”

Pilgrimages, Alberuni noted, are not obligatory for the Hindus, but ‘”facultative and meritorious’. Most of the venerated places are located in the cold regions round mount Meru. About the construction of holy ponds, let me quote his own words:

“In every place to which some particular holiness is ascribed, the Hindus construct ponds intended for the ablutions. In this they have attained to a very degree of art, so that our people (the Muslims), when they see them, wonder at them, and are unable to describe them, much less to construct anything like them. They build them of great stones of enormous bulk, joined to each other by sharp and strong cramp-irons, in the form of steps (or terraces) like so many ledges; and these terraces run all around the pond, reaching to a height of more than a man’s stature. On the surface of the stones between two terraces they construct staircases rising like pinnacles. Thus the first step or terraces are like roads (leading up and down). If ever so many people descend to the pond whilst others ascend, they do not meet each other, and the road is never blocked, because there are so many terraces, and the ascending person can always turn aside to another terrace than on which the descending people go. By this arrangement all troublesome thronging is avoided.”

No discussion of India would be complete without observation of the contemporary caste system. Alberuni provides much insight on this theme as well.Socially he describes the rituals as prescribed in the Dharmasastras, and while he criticizes the rigours of these rituals, he also points out that such inequalities are shared by other cultures as well. It is arguable though, that his views are influenced by his being a Sanskritist, i.e. based on the textual sources rather than ground realities.

He describes the traditional division of Hindu society along the four varnas and the antyaja—who are not reckoned in any caste but ‘only as members of a certain craft or profession’. The antyajas, according to Alberuni, were divided into eight classes (i.e. fuller, shoemaker, juggler, basket and shield maker, sailor, fisherman, hunter of wild animals and birds and weaver) according to their professions (guilds) who freely intermarry with each other except with the fuller, shoemaker and the weaver. The antyajas however according to him ‘lived near the villages and towns of the four castes, but outside them’.

He further mentions hadi, doma, candela and badhatau(?) who were outside the pale of the castes and guilds and were ‘occupied with dirty work, like cleansing of the villages and other services’ and were taken to be illegitimate descendants of a shudrafather and a brahmin mother.

On the eating customs of the four castes, he observed that when eating together, they form a group of their own caste, one group not comprising a member of another caste. Each person must have his own food for himself and it is not allowed to eat the remains of the meal. They don’t share food from the same plate as that which remains in the plate becomes after the first eater has taken part, the remains of the meal.

Alberuni also mentions the dresses worn by the Indians. He says:

“They use turbans for trousers. Those who want little dress are content to dress in a rag of two fingers’ breadth, which they bind over their loins with two cords; but those who like much dress, wear trousers lined with as much cotton as would suffice to make a number of counterpanes and saddle-rugs. These trousers have no (visible) openings, and they are so huge that the feet are not visible. The sting by which the trousers are fastened is at the back.

Their sidar (a piece of dress covering the head and the upper part of breast and neck) is similar to the tousers, being fastened at the back by buttons.

The lappets of the kurtakas (short shirts from the shoulders to the middle of the body with sleeves, a female dress)have slashes both on the right and left sides.

They keep the shoes tightvtill they begin to put them on. They are turned down from the calf before walking(?).”

• Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi