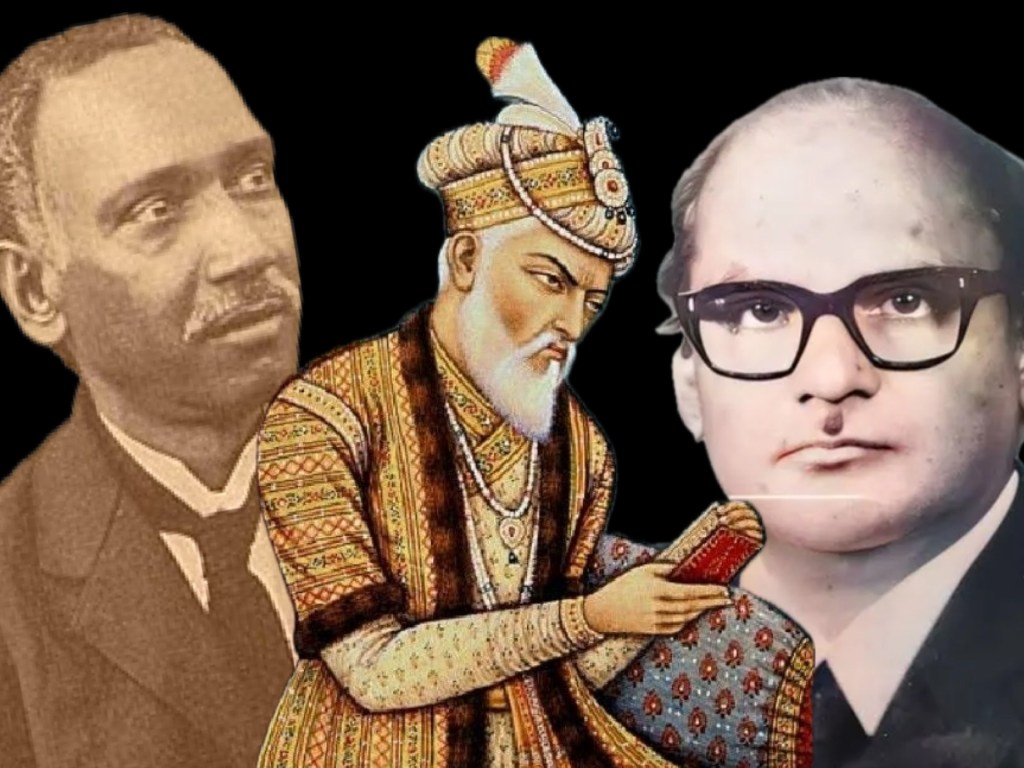

Aurangzeb, Shivaji, and the Evolution of Historical Understanding: From Jadunath Sarkar to M Athar Ali

My talk today addresses two related questions. First, how should we understand Sarkar’s own approach to Aurangzeb and Shivaji? Writing under colonial rule and bearing knighthood, was he a “colonial historian”? Was he following a British template—belittling Aurangzeb as a fanatic while elevating Shivaji as a Hindu hero—much as Rushbrook Williams, in another context, contrasted Babur with Rana Sanga? Or was Sarkar simply extracting what he believed the sources compelled him to conclude? Second, what has changed in our assessment of Aurangzeb since Sarkar—what has modern research altered, corrected, or complicated?

There is little doubt that Jadunath Sarkar was among the tallest historians of his age, and one whose scholarly seriousness is beyond dispute. When he undertook Mughal history, he first equipped himself with the language of the sources. He did not rely on translated Persian texts; he built his arguments from what the primary sources revealed. He mastered Persian and the scripts in which Mughal documents circulated—including difficult hands such as khaṭṭ-i shikast. The Irvine Collection housed at the British Library contains materials painstakingly collected, acquired, and copied by Sarkar. He was perhaps among the earliest historians to work systematically with the Akhbārāt-i Dārbar-i Muʿallā, a rich set of Mughal news-reports and official documentation. Many documents acquired or copied by him later came to be housed at Sitamau. His collaboration with two major contemporaries—G. S. Sardesai for Marathi materials and Raghubir Singh of Sitamau—is now well documented, notably in K. C. A. Raghavan’s History of Men: Jadunath Sarkar, G. S. Sardesai, Raghubir Singh and Their Quest for India’s Past (HarperCollins, Noida, 2020), one of the best recent works for understanding Sarkar’s scholarly world.

At the same time, Sarkar’s intellectual formation belonged unmistakably to a particular moment. In one of his writings, Rudrangshu Mukherjee called Sarkar a product of his times, describing him as “the last representative of a long intellectual line that began with (Raja) Rammohan Roy,” a lineage that could hail British rule as a providential end to years of “Muslim tyranny.” Sarkar himself, in the second volume of his History of Bengal (Dacca, 1948), described British rule as “the beginning of a glorious dawn, the like of which the history of the world has not seen anywhere.” He also suggested that European success in India lay not primarily in perfidy or superior weapons, but in scientific temper and organisational ability.

More recently, Dipesh Chakrabarty, in The Calling of History: Sir Jadunath Sarkar and His Empire (University of Chicago Press, 2015), has described Sarkar as “a child of the empire” who embraced its highest abstract ideals and struggled to give Indian history a scientific and academic status, in opposition to what he saw as the shortcomings of popular history.

Sarkar’s productivity was extraordinary. He wrote extensively on the centuries preceding the “glorious dawn” of British rule: four books and 158 essays and addresses in Bengali; 17 books (some multi-volume) and around 260 research papers in English; and more than a hundred essays for newspapers and magazines. He also translated into English a number of Persian (and even French) documents (see Aniruddha Ray, Jadunath Sarkar, Paschim Banga Bangla Akademi, Kolkata, 1999, pp. 70–118). As A. L. Basham observed (“Sir Jadunath Sarkar, C.I.E.,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 90, 1958, pp. 222–23), Sarkar’s greatness lay especially in bringing to light a vast range of primary Mughal materials.

For the late seventeenth century—and for the political turbulence of that age—it is impossible to bypass Sarkar’s multi-volume History of Aurangzeb or his work on Shivaji Maharaj. In Sarkar’s framing, the reign of Aurangzeb was deeply marked by the emperor’s personal religious views and inflexible beliefs. Aurangzeb, for him, was an orthodox Muslim who pursued discrimination and persecution of Hindus; alienated communities, Sarkar argued, responded with resistance to the Mughal state. Alongside what he described as the “deterioration” in the character of the king and the nobility, Sarkar proposed that there was a discernible “Hindu reaction” visible in the Rathor, Bundela, Maratha, and Sikh revolts.

This emphasis on the individual—on personal character as the engine of historical causation—was in keeping with the historiographical temper of his age and aligns in important ways with what William Irvine had advanced in his work on the Later Mughals. In that framework, history turns on the moral and political qualities of individuals: Akbar builds empire because of tolerance; Aurangzeb presides over decline because of intolerance.

Yet Sarkar, precisely because he was a historian of substance, also acknowledged Aurangzeb’s strengths. He wrote of him:

“[Aurangzeb] was free from vice, stupidity or sloth. His intellectual keenness was proverbial…he took to business of governing with all the ardour which men usually display in the pursuit of a pleasure…His patience and perseverance were as remarkable as his love for discipline and order. In private life he was simple and abstemious like a hermit. He faced the privations of a campaign or a forced march as uncomplainingly as the most reasoned private…Of the wisdom of the ancients, which can be gathered for ethical books, he was a master.”

Alongside Aurangzeb, Sarkar’s Shivaji and His Times (first published in 1919) consolidated his reputation as a leading historian. It was not merely a political biography but also a sustained enquiry into Maratha society and government, with attention to economic and foreign policy. Sarkar also examined why Shivaji failed, in his view, to build a durable state. He highlighted the weakening effects of caste, criticised incessant aggressive warfare, and was sceptical of over-reliance on intrigue and diplomatic manoeuvre.

Sarkar also noted tensions within Maratha society: Shivaji’s experience of humiliation at the hands of Brahmins, despite his own devotion to Brahmanical defence and prosperity; their insistence on treating him as a Shudra; and the role of Balaji Avji, a Kayastha leader, whose own social experience stood at odds with Brahmanical dominance.

He was equally unsparing about economic policy. Sarkar pinpointed Shivaji’s repeated plunder of Surat as a strategy that frightened away wealth and trade, progressively impoverishing the city and drying up a potential source of resources. Revenues such as chauth and sardeshmukhi, he argued, could not serve as stable fiscal foundations.

As with Aurangzeb, Sarkar explored Shivaji’s personal life and ethical posture: free from vice, austere, devoted to religion and holy men, and yet, in Sarkar’s account, notably impartial—respecting Hindu and Muslim holy men alike. He also stressed Shivaji’s charisma as a leader of men. Despite being a devout Hindu, Shivaji had a number of Muslim commanders—Munshi Haider, Siddi Sambal, Siddi Misri, Siddi Halal, Nur Khan, and Daulat Khan—and he gave legal recognition to Muslim qazis within his dominion—details that sit uneasily with modern political caricatures.

If Sarkar’s Aurangzeb unsettled those who wished for an uncomplicated Mughal apology, Sarkar’s Shivaji disappointed many nationalists. As Chakrabarty notes, Sarkar’s readers could be deeply dismayed by his criticism of the Maratha hero; his “dispassionate assessments” refused to conceal darker episodes. He was explicit, for instance, about Shivaji’s acquisition of Javli through the killing of members of the Morey clan.

Was Sarkar, then, essentially writing as a British loyalist? Did he work with a communal template? The evidence is more complicated. Sarkar discomforted apologists on both sides. The more persuasive reading is that he was an empiricist working within the limits—and the habits—of the sources available to him. Raghavan captures this tradition neatly when he describes Sarkar as a judge rather than a lawyer: dispassionately viewing evidence and pronouncing judgement, not simply marshalling facts for a predetermined conclusion. Sarkar hunted down sources, translated them, and extracted embedded evidence; he integrated topography into narrative and analysed outcomes with a craftsman’s discipline. He also often offered counterfactual alternatives—what might have been done differently—most famously in his discussion of possible imperial choices in 1679 during the Rathor crisis.

Sarkar’s method can be illustrated in his use of parallel traditions: he observed that both the Sabhasad Bakhar (1697) and Persian Bijapuri histories used the term mulkgiri to describe raiding into neighbouring territories as a political ideal; Bhimsen, in the Nuskha-i Dilkusha, also used mulkgiri for Maratha raids under Shivaji and Sambhaji. Sarkar argued that Mughal mulkgiri spared co-religionists while Shivaji’s mulkgiri struck across Hindu and Muslim polities alike; he further claimed, on the basis of Sabhasad’s narrative, that Shivaji’s enterprises often amounted to plunder.

Such views—Aurangzeb’s “bigotry,” Shivaji’s “blemishes,” and the explanatory weight placed on personal character—continued to shape historical writing well into the mid-twentieth century. But by the 1950s and 1960s, Indian historiography underwent a notable shift: the centre of gravity moved from individuals to structures, from moral character to socio-economic processes, from rulerly intent to the mechanics of state and class.

In the decade after Independence, changes in method and new sources produced new perspectives. Harbans Mukhia has repeatedly noted that the publication of Irfan Habib’s The Agrarian System of Mughal India (1961) made “the ruler and his personal predilections irrelevant” to historical explanation, shifting focus from the sovereign to a ruling class driven by the imperatives of revenue extraction. Around the same time, Satish Chandra’s Parties and Politics at the Mughal Court, 1707–1740 (1959) offered a new framework to explain decline—emphasising a deepening social crisis and stresses within the jagirdari system rather than the personality of the emperor. Even earlier, in the 1950s, Mohammad Habib’s short treatise on Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni had insisted that economic motivations—temples as repositories of wealth—often mattered more than religious zeal in episodes of plunder.

During the 1970s and 1980s, scholars associated with the Aligarh School advanced this transformation further. Iqtidar Alam Khan traced Akbar’s religious policies to the growth of a cosmopolitan nobility from the early 1560s, encompassing multiple ethnicities, religions, and origins. M. Athar Ali, in The Mughal Nobility under Aurangzeb (1966), extended and reworked arguments linked to Satish Chandra’s emphasis on systemic pressures and explored what he called a cultural and ideological failure linked to the inability to adapt modern science and technology. This was a different explanatory universe from Sarkar’s “Hindu reaction” thesis.

To be fair to Sarkar, such approaches were not available—indeed, scarcely imaginable—when he wrote. “All history is contemporary history”: the historian cannot fully escape the intellectual atmosphere of the age. Sarkar’s writing was, in many ways, true to his time.

History-writing is not static; it is a dynamic process, continually moderated by new questions, new methods, and the discovery of sources previously unknown. No historian can be held responsible for materials not yet found. Since Sarkar, the location of new evidence and the adoption of new interpretive frameworks have enabled historians to revise important aspects of Aurangzeb’s reign. Let me offer a few examples.

Sarkar used two farmāns issued by Aurangzeb—one to Rasikdas and another to Muhammad Hashim—relating to revenue collection, with the latter couched in the idiom of shari‘a and invoking categories such as khums and zakat, taxes not levied in India. Subsequent research showed that the “Rasikdas” farmān was, in effect, a standardised order sent to different provinces for different diwans. Later, Irfan Habib and Shireen Moosvi argued that these documents were not evidence of religious taxation but instructions on managing a crisis of revenue collection—better understood against the backdrop of agrarian distress, including themes discussed in Francois Bernier on peasant flight. Moosvi, in particular, read the Rasikdas farmān as a practical manual for revenue officials navigating multiple obstacles to collection.

Similarly, using sources not accessible to Sarkar, Irfan Habib argued that the outbreaks associated with Nanakpanthis (1665), Jats (1669), and Satnamis (1672) were not “Hindu revolts” but uprisings rooted in agrarian pressure and heavy taxation rather than religious discrimination. The Satnamis were indeed a religious sect—known popularly as mundiyas—but they were also agriculturists and petty traders; so too were the Jats of Mathura and the Nanakpanthis of Kashmir and Punjab. Their resistance, in this reading, was driven by the economic extraction of a regressive system. M. Athar Ali interpreted these upheavals as zamindari revolts shaped by jagir transfers that intensified exploitation: jagirdars pressed zamindars, and both together squeezed the peasantry—leading to rebellion involving superior right-holders and cultivators alike. This was a major departure from Sarkar’s framing, which—given the limits of his sources—had tended to translate conflict into a Hindu–Muslim axis.

The same pattern appears in the case of the Rathor rebellion of 1679. For Sarkar, it flowed primarily from Aurangzeb’s anti-Hindu and anti-Rajput posture. Let us examine the issue first through Sarkar’s account, and then through later evidence used by Athar Ali.

In December 1678, Maharaja Jaswant Singh died at Jamrup in Afghanistan. He left no surviving son: Prithvi Singh had died in 1675. Reports reached Aurangzeb that two ranis were expectant. Jaswant Singh was also indebted to the state; Aurangzeb ordered efforts to recover dues from the deceased raja’s property, as customary practice required. At the same time, pending a final decision about the succession, Aurangzeb waited for the birth of the child. Under the Mughals, the conferring of tika carried political-administrative meaning: it was the emperor’s recognition of a particular claimant as ruler of a territory.

After Jaswant Singh’s death, Rani Hadi, the chief queen, pressed for the tika to be conferred on her. But by Mughal succession practice, a widow could not receive it; and Hindu law, too, gave the widow no such standing. The Rathors thus lacked a candidate. When a son—Ajit Singh—was born, the situation changed: now there was an heir to the gaddi. Initially, Aurangzeb did not doubt Ajit’s legitimacy, as seen in the cancellation of the assignment of Pokhran to Askaran once news arrived that a son had been born. But the administrative difficulty remained: the tika could not be conferred on an infant. Aurangzeb therefore ordered Jodhpur to be included in the khalisa.

The Rathors resented this. Durgadas, son of Askaran Rathore, fled with Ajit Singh to Jodhpur. Rani Hadi protested that no bhumiya (zamindar) had ever been dispossessed from their watan. Why should Rathors—who had served the empire so loyally—be asked to leave Jodhpur at the moment the late raja’s ceremonies were still underway? Durgadas and Sona Bhati demanded the revocation of khalisa incorporation and asked that the tika be conferred on Ajit Singh. Their resentment was genuine, but the Mughal technical problem was also real.

Sarkar, while conceding the technical hitch—no tika for widow or infant—argued that Aurangzeb could have conferred the tika on Inder Singh, grandson of Amar Singh (Jaswant’s elder brother), a near blood relation, a seasoned commander in the Deccan with a mansab of 1500/1000. Aurangzeb, Sarkar suggested, did not do so because he wanted to deprive Hindus of a powerful centre that might resist his anti-Hindu policy. When protests intensified, Aurangzeb, Sarkar said, began doubting Ajit’s legitimacy, claiming he might be the son of a milk-woman or maidservant.

Later evidence complicates this story. Fortunately, the dispatches of the waqi‘a-nigar of Ajmer sent to the emperor survive in a two-volume manuscript in the Asafiya Library, Hyderabad; a transcript exists in our own library. These reports are written for the emperor’s eyes and provide near-contemporary, first-hand information about events in 1679–80. They were not discovered in Sarkar’s time. M. Athar Ali used these dispatches in his PIHC paper (Delhi, 1961) on the causes of the Rathor rebellion.

According to this evidence, Aurangzeb—taking account of Rathor reaction—cancelled the order of khalisa incorporation and conferred the tika on Inder Singh, reportedly for a consideration of 36 lakhs of rupees. Another claimant, Karan Singh, offered 45 lakhs but was rejected—suggesting that money alone cannot explain the decision. After Inder Singh’s appointment, Rathor resistance sharpened dramatically. Rani Hadi even petitioned Aurangzeb that if he wished temples destroyed, the Rathors would comply, but the appointment of Inder Singh must be revoked; she preferred khalisa incorporation to Inder Singh’s rule. Aurangzeb rejected this petition. She then took the extreme step of seeking clarification through the court of Qazi Hamid, who boycotted the petition.

Two questions arise: why was Inder Singh so unacceptable? Because Inder Singh belonged to the line of Amar Singh, whom Jaswant Singh’s family had earlier deprived and humiliated. Durgadas, other Rathor leaders, and the widows feared revenge and retribution if Inder Singh entered Jodhpur. These internal tensions were known to Aurangzeb, while Sarkar seems either unaware of them or does not foreground them. When Aurangzeb refused to withdraw the appointment, the Rathors declared they would not allow Inder Singh to enter. In short, the rebellion’s core issue was Inder Singh’s appointment, not khalisa incorporation per se.

This also exposes a weakness in Sarkar’s interpretation. If Aurangzeb truly wanted to weaken a “Hindu centre,” he could have named Ajit Singh—however doubtful in legitimacy—as raja, with an imperial administrator governing until the child matured. That would have pacified Rathor sentiment while ensuring Jodhpur remained politically dependent. Aurangzeb did not do so, arguably because he wanted Jodhpur to function effectively: the Rathors supplied excellent soldiers, and Jodhpur’s location on the Agra–Gujarat trade route made stable law-and-order strategically important. Sarkar thus misidentified the immediate cause: the bitterness of Durgadas, Sona Bhati, and Rani Hadi was directed primarily against Inder Singh. When the emperor held firm, the Rathors told the qila‘dar of Jodhpur, Iftekhar Khan, to depart—they were beginning rebellion.

All this brings us back to the larger question: was Aurangzeb as bigoted as Sarkar portrayed him? Modern research—from M. Athar Ali and M. L. Bhatia to Audrey Truschke—has often moderated the earlier picture and argued for a more nuanced emperor. Many scholars, from Sarkar and S. R. Sharma to Athar Ali, Bhatia, and Truschke, have approached this theme; some—Shibli Nomani, Sharma, and Sarkar—presented Aurangzeb as a bigot, while others offered more complex readings.

Importantly, Aurangzeb was not perceived by his contemporaries as a hard-core zealot in the manner later projected. Several contemporaneous historians—including Hindu writers such as Bhimsen (Nuskha-i Dilkusha) and Isardas Nagar (Futuhat-i Alamgiri)—do not construct him in that idiom. The “bigot” image hardens later, particularly from the late eighteenth century onward, and gains firmer footing in colonial and nationalist historiography.

The War of Succession, as we now recognise, was not fought on communal grounds or as a clash between Dara Shukoh’s tolerance and Aurangzeb’s supposed anti-Hindu ideology. Aurangzeb did not claim to be defending Islam in 1658, nor did he treat Islam as being threatened by Shahjahan or Dara. In the early years after accession, we do not see blanket discrimination against Hindus or Rajputs. Aurangzeb appointed Raja Raghunath Singh (a Khatri) as diwan of the empire—an appointment without close precedent since Todarmal’s death. He also appointed two non-Muslim subahdars to key provinces: Maharaja Jaswant Singh in Gujarat—despite his earlier opposition in the succession war—and Mirza Raja Jai Singh as viceroy of the Deccan, an office often reserved for princes of royal blood. If one insists on the language of discrimination, one must admit that in these years it often operated in favour of Rajputs, not against them. Promotions to Rajputs were not inferior to those given to other segments of the nobility.

A further restraint shaped Aurangzeb’s early policy: as long as Shahjahan lived, Aurangzeb could not afford to alienate powerful factions, because an alternative claimant remained available. The institution of monarchy had been compromised by the very manner of Aurangzeb’s accession; he therefore moved cautiously, aware that the precedent of imprisoning the emperor could legitimate future rebellions. He also had to fulfil commitments made during the war of succession and deliver on the expansionist promise that supported noble fortunes. Hence the early expeditions in multiple directions—many of which ended badly: Mir Jumla’s death in Assam, Shaista Khan’s humiliation in the Deccan, Jai Singh’s diplomatic success at Purandhar in 1665 followed by the loss of its fruits after Shivaji’s escape from Agra.

Military disappointments set off a chain reaction: the Yusufzai revolt (1667), Afridi revolt (1674), the Jat rebellion (1669), the Satnami uprising (1672), and Shivaji’s coronation. Aurangzeb’s political record, at best, was mixed. The weakening of monarchy demanded compensation from another source, and it is here that Aurangzeb’s emphasis on shari‘a idioms and clerical support must be located. He deployed it with such finesse that not only contemporaries but later historians could be misled. The failure of Prince Akbar’s rebellion—ending in flight—illustrates how far Aurangzeb succeeded, at least temporarily, in consolidating sections of the Muslim aristocracy behind the throne. It is in this context that measures like the imposition of jizya in 1679 acquire a political logic: why was it not imposed from 1658 onward, if the aim was purely theological?

Debating Aurangzeb’s leanings—religious orthodoxy or political pragmatism—one must ask whether he truly intended, as Sarkar suggested, the establishment of dār al-Islām in India, mass conversion, and annihilation of dissent, or whether, as Ishtiyaq Husain Qureshi, Shri Ram Sharma, and others proposed, he aimed at rigid adherence to shari‘a and the undoing of Akbar’s damage. Such portrayals struggle to explain empirical features of his reign—such as the increasing proportion of Rajput mansabdars and the prominence of figures like Raghunath Ray Kayastha as diwan-i kul, honoured by Aurangzeb and praised in the Ruqa‘at-i Alamgiri.

Aurangzeb did increase the visibility of the ʿulamāʾ and promulgate measures overtly aligned with sharīʿah norms; Khafi Khan remarks that he gave qazis extensive powers in civil administration, provoking jealousy among leading nobles. Prohibitions on intoxicants, restrictions on certain pilgrimages, discouragement of music and dancing, withdrawal of patronage from astrologers, and attempts to regulate taxation in sharīʿah terms all strengthened later claims that Aurangzeb was an orthodox champion—some even seeing in him the triumph of Sirhindi’s reforms. But the record also indicates the limits of such a reading: the ʿulamāʾ were state employees, the system was riddled with rivalries and corruption, enforcement was uneven, and Aurangzeb repeatedly subordinated clerical opinions to imperial authority—dismissing qazis and shaikh ul-Islams who resisted his political aims.

Even emblematic achievements such as the commissioning of the Fatawa-e Alamgiri can be read less as a radical break than as codification for guidance, while actual judicial practice still depended on individual qazi interpretations and the interplay of imperial edict and custom. In many respects, Aurangzeb’s policies continued Mughal precedent: clerics could be patronised, but they could not dictate the state.

The same caution applies to “early measures” often labelled religious: stopping tuladan and jharokha darshan, prohibiting wine, discouraging chahar taslim, banning astrology, restricting coloured garments, and banning music. Some historians, like R. P. Tripathi, even interpret certain actions—such as the music ban—as tied to austerity in a period of financial strain, especially when allowances of princes and princesses were curtailed.

At the rural level, policies around madad-i ma‘ash grants—mostly to Muslims—also intersected with political stresses. In the 1670s and 1680s Aurangzeb faced multiple zamindari crises; most zamindars were Hindus and many jagirdars were Muslims. To counter rural power, he could seek to strengthen Muslim landed presence and stabilise certain grants, making some permanent and hereditary—creating local counterweights to entrenched zamindari authority. Abul Fazl Ma’muri’s Tarikh-i Aurangzeb speaks of a jagirdari crisis—hama ālam bējāgīr mand—and of caution in promotions, with saved resources redistributed to consolidate support.

Jizya and temple destruction remain among the hardest issues. Jizya was discriminatory and humiliating; yet exemptions existed—Rajputs, Brahmins, and those in Mughal service among them—and it was graded by income. Some historians argue that its fiscal yield barely exceeded collection costs and that much was lost to corruption, while its symbolism mattered more than revenue. Temple destruction, too, is documented: orders in 1669 and again in 1679–80, including attacks on major shrines. At the same time, there is also extensive evidence of grants to Hindu religious institutions—temples, maths, Brahmins, pujaris—renewed land grants, donations such as ghee for temple lamps, gifts to Sikh institutions, and continued madad-i ma‘ash grants even to Nathpanthi yogis in places like Didwana and Nagor.

How do we reconcile destruction and patronage? One explanation advanced in modern scholarship is reprisal and politics rather than blanket iconoclasm—attacks linked to rebellion, local disloyalty, or political misconduct, while loyal and widely venerated institutions could be spared. In this reading, the destruction of Kashi Vishwanath, Keshav Dev at Mathura, and several Rajasthan temples is placed within local contexts of revolt, suspected collaboration, and shifting alliances. Jizya and selective temple destruction were discriminatory; yet the coexistence of grants and exemptions complicates any single-axis narrative.

Contemporary evidence is instructive here. Bhimsen, an eyewitness to the Deccan campaigns and a sharp critic of Aurangzeb’s strategy—especially the focus on fort-taking while Marathas controlled the countryside—does not build his critique primarily on religious grounds. He mentions jizya without rancour. Hindu writers such as Bhimsen, Isardas Nagar, and Sujan Rai Bhandari do not foreground religious persecution in the manner later historiographies do. This silence does not “prove” innocence, but it does suggest that the explanatory weight placed on religious policy in later communalised narratives may not align with the emphases of seventeenth-century observers.

Athar Ali’s broader caution is valuable: to judge the effects of Aurangzeb’s religious policy, one should not project the India of the nineteenth century—shaped by modern national and religious consciousness—onto the seventeenth. Loyalties to caste, clan, region, and master often overrode confessional identity. Moreover, policy prescriptions on paper could not always be implemented rigorously on the ground; temple destruction, in particular, could be negotiated, resisted, or locally adjusted, as official news-reports suggest. In the short term, the effects of religious measures may have been limited compared to deeper structural problems—fiscal pressure on peasantry, jagirdari stresses, and the strategic failures of the Deccan.

I have highlighted only some themes to show how Aurangzeb is assessed differently after Sarkar, and how our understanding of his reign has undergone a sea-change in recent decades. Does this mean Sarkar’s formulations stand diminished? Does it mean he wrote a communal history? Perhaps not. Sarkar was a historian working within the boundaries of the sources then known and the questions then considered central. As new sources were located and new perspectives developed, conclusions shifted—as they must. History can never be definitive or perfect; it reveals only what we ask of it, and depends upon where, and how, we seek our answers.

• Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi