Monotheism is the belief in the existence of one god, as distinguished from polytheism, the belief in more than one god. The earliest known instance of monotheism dates to the reign of Akhenaton of Egypt in the 14th century BCE. Monotheism is characteristic of the Abrahamic religions, (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), but is also present in Neoplatonism, in the Advaita, Dvaita and Vishishtadvaita philosophies of Hinduism and in Sikhism and it is difficult to delineate from notions such as pantheism and monism.

Bhakti, (devotion or portion) in practice signifies an active involvement by the devotee in divine worship. The term is often translated as “devotion”, though increasingly “participation” is being used as a more accurate rendering, since it conveys a fully engaged relationship with God. One who practices bhakti is called a bhakta, while bhakti as a spiritual path is referred to as bhakti marga, or the bhakti way. Bhakti is an important component of many branches of Hinduism, defined differently by various sects and schools.

Bhakti emphasises devotion and practice above ritual. Bhakti is typically represented in terms of human relationships, most often as beloved-lover, friend-friend, parent-child, and master-servant. It may refer to devotion to a spiritual teacher (Guru) as guru-bhakti, to a personal form of God, or to divinity without form (nirguna). Different traditions of bhakti in Hinduism are sometimes distinguished, including: Shaivas, who worship Shiva and the gods and goddesses associated with him; Vaishnavas, who worship forms of Vishnu, his avatars, and others associated with; Shaktas, who worship a variety of goddesses. Belonging to a particular tradition is not exclusive—devotion to one deity does not preclude worship of another.

The Bhagavad Gita is the first text to explicitly use the word “bhakti” to designate a religious path, which the Bhagavata Purana develops more elaborately. The so-called Bhakti Movement saw a rapid growth of bhakti beginning in Southern India with the Vaisnava Alvars (6th-9th century CE) and Saiva Nayanars (5th-10th century CE), who spread bhakti poetry and devotion throughout India by the 12th-18th century CE. Bhakti influence in India spread to other religions, coloring many aspects of Hindu culture to this day, from religious to secular, and becoming an integral part of Indian society.

The Bhakti movement, started sometimes from 8th Century by Shankara and Ramananda in the South, emphasized the unity of all the different Hindu gods, the surrender of the self to God, equality and brotherhood of all people, and devotion to God as the number one priority of life. One of the most important impacts of the Bhakti movement on Indian society was the rejection of the caste system.

During the 14-17th centuries, a great bhakti movement swept through Central and Northern India, initiated by a loosely associated group of teachers or sants. Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Vallabha, Surdas, Meera Bai, Kabir, Tulsidas, Ravidas, Namdeo, Dnyaneshwar, Tukaram and other mystics spearheaded the Bhakti movement in the North. They taught that people could cast aside the heavy burdens of ritual and caste, and the subtle complexities of philosophy, and simply express their overwhelming love for God. This period was also characterized by a spate of devotional literature in vernacular prose and poetry in the ethnic languages of the various Indian states or provinces.

While many of the bhakti mystics focused their attention on Krishna or Rama, it did not necessarily mean that the sect of Shiva was marginalized. In the thirteenth century Basava founded the Vira-Shaiva school or Virashaivism. He rejected the caste system, denied the supremacy of the Brahmins, condemned ritual sacrifice and insisted on bhakti and the worship of the one God, Shiva. His followers were called Vira-Shaivas, meaning “stalwart Shiva-worshipers”.

The Saiva-Siddhanta school is a form of Shaivism found in the south and is of hoary antiquity. It incorporates the teachings of the Shaiva nayanars and espouses the belief that Shiva is Brahman and his infinite love is revealed in the divine acts of the creation, preservation and destruction of the universe, and in the liberation of the soul.

Seminal Bhakti works in Bengali include the many songs of Ramprasad Sen. His pieces are known as Shyama Sangeet. Coming from the 17th century, they cover an astonishing range of emotional responses to Ma Kali, detailing philosophical statements based on Vedanta teachings and more visceral pronouncements of his love of Devi. Using inventive allegory, Ramprasad had ‘dialogues’ with the Mother Goddess through his poetry, at times chiding her, adoring her, celebrating her as the Divine Mother, reckless consort of Shiva and capricious Shakti, the universal female creative energy, of the cosmos.

Amongst the most prominent monotheistic movements and saintly figures one may name the following:

- The Kabir Panthis – which included the teachings of Sant Kabir and Sant Ravidas

- The Nanak Panthis – or the philosophy of monotheistic faith as propounded by Guru Nanak and his followers;

- Dadu Panthis – that is Dadu and his disciples; and

- Other Vaishnava movements which talked of monotheism, eg. The Chaitanya Movement.

Let us start with the Vaishnava movements.

Surdas (1478/1479 – 1581/1584 in Braj, near Mathura), was an Indian saint and composer.

What little knowledge we have of Surdas’s life comes from Ain-e-Akbari and Munshiat-e-Abul-Fazl, both written during the time of Akbar

Tulsidas (also Tulasidas, Gosvāmī Tulsīdās, Tulasī Dāsa) (1532 – 1623) was a great Awadhi bhakta (devotee), philosopher, composer, and the author of Ramcharitmanas, an epic poem and scripture devoted to Rama.

Like Ramanuja, Tulsi believes in a supreme personal God, possessing all gracious qualities (sadguna), as well as in the quality-less (nirguna) neuter impersonal Brahman of Sankaracharya; this Lord Himself once took the human form, and became incarnate, for the blessing of mankind, as Rama. The body is therefore to be honored, not despised. The Lord is to be approached by faith (bhakti) disinterested devotion and surrender of self in perfect love, and all actions are to be purified of self-interest in contemplation of Him. Show love to all creatures, and thou wilt be happy; for when thou lovest all things, thou lovest the Lord, for He is all in all. The soul is from the Lord, and is submitted in this life to the bondage of works (karma); Mankind, in their obstinacy, keep binding themselves in the net of actions, and though they know and hear of the bliss of those who have faith in the Lord, they don’t attempt the only means of release. The bliss to which the soul attains, by the extinction of desire, in the supreme home, is not absorption in the Lord, but union with Him in abiding individuality. This is emancipation (mukti) from the burden of birth and rebirth, and the highest happiness. Tulsi, as a Saryupareen Brahmin, venerates the whole Hindu pantheon, and is especially careful to give Shiva or Mahadeva, the special deity of the Brahmins, his due, and to point out that there is no inconsistency between devotion to Rama and attachment to Shiva (Ramayana, Lankakanda, Doha 3). But the practical end of all his writings is to inculcate bhakti addressed to Rama as the great means of salvation and emancipation from the chain of births and deaths, a salvation which is as free and open to men of the lowest caste as to Brahmins.

However it is important to understand that for Tulsidas “doctrine” is not so important. Far more relevant is practise, the practise of repeating Rama-Nama, the name of the Rama. In fact, Tulsidas goes as far as to say that the name of Rama is bigger than Rama Himself (कहउँ नामु बड़ राम तें निज बिचार अनुसार,). Why is the name of Rama bigger than Rama? Because “Rama” is a mantra, a sound, the repetition of which can lead one to higher states of consciousness. Because the name itself contains Lord Rama himself in it. Rama itself means the one which is present in every atom of this universe (Ramta sakal jahan).

Gaudiya Vaishnavism (also known as Chaitanya Vaishnavism and Hare Krishna) is a Vaishnava religious movement founded by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1534) in India in the 16th century. “Gaudiya” refers to the Gauḍa region (present day Bengal/Bangladesh) with Vaishnavism meaning “the worship of Vishnu”. Its philosophical basis is primarily that of the Bhagavad Gita and Bhagavata Purana, as well as other Puranic scriptures and Upanishads such as the Isha Upanishad, Gopala Tapani Upanishad, and Kali Santarana Upanishad.

The focus of Gaudiya Vaishnavism is the devotional worship (bhakti) of Radha and Krishna, and their many divine incarnations as the supreme forms of God, Svayam Bhagavan. Most popularly, this worship takes the form of singing Radha and Krishna’s holy names, such as “Hare”, “Krishna” and “Rama”, most commonly in the form of the Hare Krishna mantra, also known as kirtan. The movement is sometimes referred to as the Brahma-Madhva-Gaudiya sampradaya, referring to its traditional origins in the succession of spiritual masters (gurus) believed to originate from Brahma. It classifies itself as a monotheistic tradition, seeing the many forms of Vishnu as expansions or incarnations of the one Supreme God, adipurusha.

Kabir Panthis:

Kabir, whose dohas or poems have been sung for the last 500 years. A Vaishnava bhakta to Hindus, a pir to the Muslims, a bhagat to the Sikhs and an avatar of the Supreme Being to the Kabir Panthis, Kabir was a radical social reformer, who attacked the principles of untouchability, caste distinctions, all forms of social discriminations and ritualism.

There were three major traditions of Kabir’s compositions, the bijak, the panchavani and the Granth Sahib. In his common padas he reveals emphasis on the unity of God, the Creator of the universe. In them, God is the painter, the weaver and the thug. The stars in the sky are witness to his Art, the sun and the moon, to his Light in the entire universe. As a weaver (kori) his network spreads all over the universe, the earth and the sky are his workshops, the sun and the moon his shuttles. God (Har) is a great thug who deceives the whole World: whose son? Whose father? Who dies and who is to be blamed? Whose wife? Whose husband? Once deception is recognized for what it is, then it is no deception. God is recognized in and around the universe.

Kabir, like other low-born saints of that time represented a wholesale rejection of Hinduism and Islam. He demanded an acceptance of God but rejection of all formal religions.

The Hindu when dying cries Ram! The Musalman ‘O Khudai!’

Says Kabir, he (alone) is alive, who never accepts this duality!

Kabir then becomes Kasi, Ram becomes Rahim

Moth (coarse grain) becomes fine flour, and Kabir sits down to enjoy it!

That is why during the 16th Century Kabir was recognized not as a Hindu or Muslim, but as a muwahhid. Abdul Haq Muhaddith reports a converstion between his grandfather and father as early as 1522 in which Kabir was nomenclated so. This is how he is defined in Dabistan-i Mazahib as well.

The unity of God becomes for Kabir the means of comprehension of the unity of Man; and so, there comes an absolute rejection, explicit and vocal, not only of the concept and practice of purity and pollution of the caste system, but also of conventional mode of worship and all ritual.

Sant Ravidas (1450-1520) was a chamar, ‘the carrion remover’ dhuvantar dhor, who also lived at Benares. His God was also Omnipresent. But he was with and without attributes (nirguna-saguna) at the same time. He had no fixed abode and was unique (anupa) his essence is in his naam: Ram naam or naam-narayana. In a verse God is compared to beautiful silk, while Ravidas himself is a silkworm that dies when it leaves his cocoon. Human life and world are not eternal (sach): One has to break this coming and going (avagaman) by recognizing the eternity of God. Ravidas also gives lot of importance to ‘Knowledge’ (gyan), and sang for loving devotion (prem bhakti) and believed that the difference of caste had no meaning. An out caste or chandal can become a bhagat.

The Nanak Panthis:

A Khatri by birth, Nanak was a contemporary of Babur. Like Kabir, he was against the caste system and ritualism. No one was high or low on the basis of birth / caste. Nanak himself identified with the lower castes and untouchables and placed the sudras and untouchables at par with Brahmans and khatris. Similarly women were placed at par with men.

For Nanak, Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh are created by God himself, who himself is the Creator, Preserver and Destroyer. Vedas, Puranas, Smritis and Shastras, none was a ‘revealed’ book. Thus it was a virtual rejection of traditional deities and religious texts. Reading of scriptures was a waste of time. There was no merit in rituals like pilgrimage and hom (ritual fire). The pandit only dealt with externalities and was like a spider who weaves its web living and dying upside down. His sacred thread, dhoti and rosary are useless. So was the yogi: Nanak was against renunciation.

He rejected the idea of re-incarnation: thus a rejection of Rama & Krishna as deities.

His attitude towards ulema and mashaikh was similar. Just as thousands of Brahmas, Vishnus and Shivas are created, so are millions of Muhammads. Quran and other texts were no better than the Vedas / Puranas. However, he showed preference to Sufis: those who want to become true Musalmans, should first adopt the path of the Auliya, treating renunciation as the file that removes rust. But then he reminds the Shaikhs that only God is everlasting.

God, to Nanak, was eternally unchanging Formless One. He had no material sign and was beyond the reach of human intellect. He was boundless, beyond time, beyond seeing, infinite, not reachable, beyond description, eternally constant, unborn, self existent and wholly apart from creation. He is the only One, there is no second, there is no other. He possesses unqualified power and absolute authority. He is ‘within’, and He is ‘without’. The ocean is the drop, and the drop is in the ocean. He stands revealed in his creation.

Loving devotion and dedication to God is true bhakti without which there is no liberation. Bracketed with bhakti is bhay (awe). God’s awe is the remedy for the fear of death. He who lodges God’s fear in his heart becomes fearless.

In contrast to the ‘truth’ of God, his creation is ‘false’ – who keeps attached to the creation suffers from dubidha (misery).

Nanak considered himself as God’s herald (tabal-bāz) to proclaim His Truth. Thus he assumes the formal position of Guru (a guide) and admitted disciples who would then practice corporate worship (sangat) and communal meals (langar). The believers would contribute in cash, kind or service (kar seva).

As there was a rejection of scriptures, worship would be performed through his own compositions (japu ji).

Nanak died at Kartarpur in 1539 and chose his successor from amongst his disciples. Lehna was installed as the Guru and was entitled Guru Angad (1539-52). He popularized gurmukhi, a nes script. He composed his writings in the name of ‘Nanak’.

He was followed by Guru Amardas (1552-74) who founded a new centre on the route from Lahore to Delhi: Goindwal. He underlined the importance of true association (sat-sangat) of his followers who came to the door of the Guru (Guruduara) for singing shabad of the Guru.

When Amardas died, he installed his son-in-law Bhai Jetha as Guru Ramdas (1574-81) who was responsible to dig a tank (sarovar) ‘a divine pool filled with the nectar of immortality (Amritsar). Initially this city was called Ramdaspur.

Ramdas was succeeded by Guru Arjan (1581-1606) who was opposed by his elder brother Prithi Chand. During his period, the Harmandir (Temple of God) was built in the midst of the Amritsar and a Granth was compiled in 1604.

Dadu (1544-1603):

He was a dhuniya (cotton carder) and was born in a Muslim family. His teachings are contained in his Bāni. He, like Kabir, Nanak and others, rejected the Vedas, the Vedantic philosophy, ritualism and formalism, priesthood, idolatory, the use of rosary, pilgrimages and ceremonial ablutions, and the caste and the caste marks. According to him, Shiva, Vishnu and Brahma were only men who had been canonized. He again and again repeated that he was neither a Hindu nor a Muslim. He rejected Quran.

He loved the merciful God as self-existent, immortal, unchangeable, fearless, pure, unimaged, unseen, infinite, incomprehensible, almighty, beautiful and joy-giving. Dadu believed that this life was separation from God. Thus the largest poem in his Bāni is called ‘Separation’ which is ‘the wail of a woman sick of love and maddened by the pain of separation’. Union or meeting with God was his goal.

He uses the epithets Allah, Khuda, Ilahi, Rahim, Karim, Malik, Sahib, Raziq, Ghani and Sultan for God. Allah is present in the heart, the body is the mosque, the five senses are the congregation, the heart is the mulla and the imam. Real worship is to take the name of the Compassionate, with the whole body as the rosary. The real fast is to acknowledge only One God.

Dadu was much close to the Islam of Sufis than to the Islam of the mullas. He rejected the idea of incarnation and was opposed to idol worship. All gods were created beings and the shakta drinks the poison of sensual ‘pleasures’.

According to him the distinction between men was on the basis of piety or devotion to God.

Like Kabir, he is mentioned by the author of Dabistan-i Mazahib: as a naddaf who lived in Naraina in Marwar during the reign of Akbar and who forbade idolatory and eating of flesh.

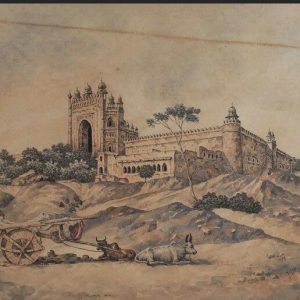

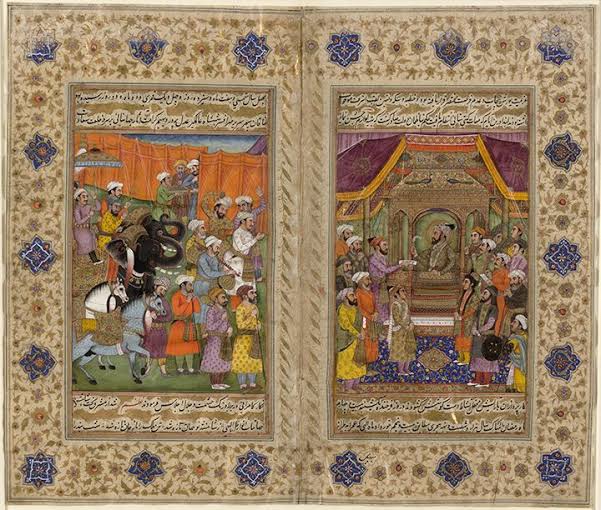

Dadu in one of the mythical stories in Dadu Janmlila of Jan Gopal (tr. Winand M. Callewaert) came to meet Akbar at Fathpur Sikri.

He was invited by Akbar through Raja Bhagwandas and Lord Rama in meditation gave him orders to go for the meeting. He first met Abul Fazl, Birbal and a Brahmin called Tulsi. During his meeting Akbar offered the saint to ask for some wish. He got the reply: “What can you do with water, if you are not thirsty?” when Akbar asked for a treasure, he got the reply: “First destroy the physical desires which tie you to worldly passions.

The true believer (momin) according to Dadu, is he whose heart is soft like a wax (mom), who knows God and does no violence.

Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi