Across the world, monuments stand as silent witnesses to the long and often complex histories of civilizations. They embody the artistic labour of generations and preserve the layered memories of societies that have risen, interacted, and transformed over centuries. When such monuments are destroyed, the act is rarely neutral. It is almost always a political gesture, an attempt to rewrite the past by obliterating its visible traces. The recent damage to historic sites in Iran during military strikes once again reminds us how vulnerable humanity’s cultural heritage remains to ideological aggression and militarized power. When viewed alongside two earlier acts of cultural vandalism, the demolition of the Babri Masjid in India in 1992 and the Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan in 2001, the disturbing parallels become unmistakable.

Iran possesses one of the most continuous and richly layered civilizational landscapes in the world. From Achaemenid ruins and Sasanian reliefs to Safavid mosques and Qajar palaces, its monuments reflect more than two millennia of cultural creativity. Structures such as the Golestan Palace in Tehran or the historic complexes of Isfahan represent not merely national symbols but global cultural treasures. Yet in contemporary geopolitical conflict, such heritage becomes dangerously exposed. Military strikes undertaken by powerful states in pursuit of strategic objectives frequently occur in or around historic urban centres, and the resulting shockwaves, fires, and structural damage do not distinguish between military installations and centuries-old monuments. Whether the destruction is intentional or dismissed as “collateral damage,” the effect remains the same: irreplaceable fragments of human history are placed at risk by the calculations of modern warfare. The willingness with which cultural landscapes are exposed to destruction reflects a troubling assumption—that the imperatives of military power can override the universal value of humanity’s heritage.

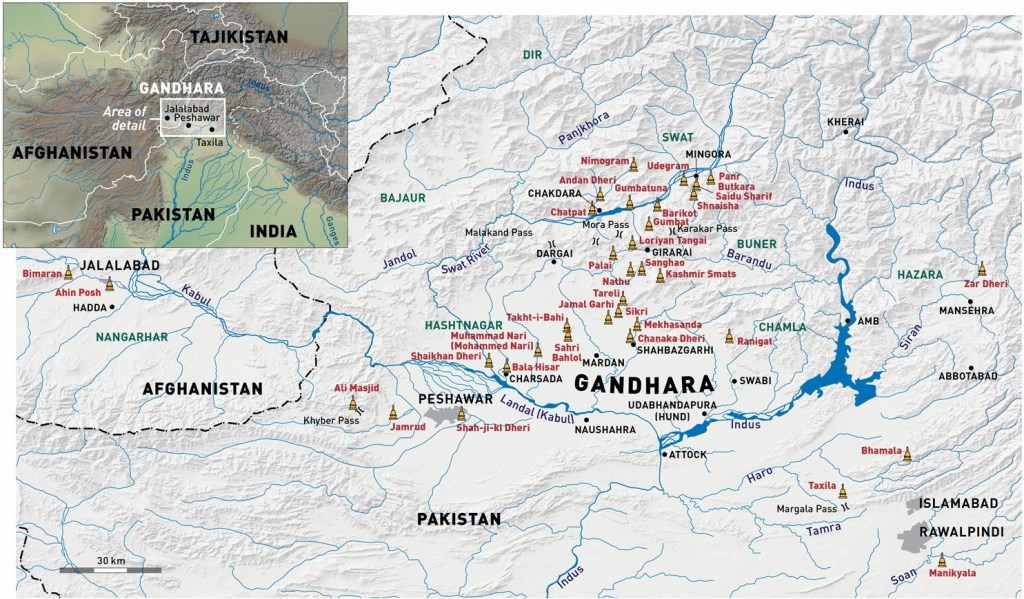

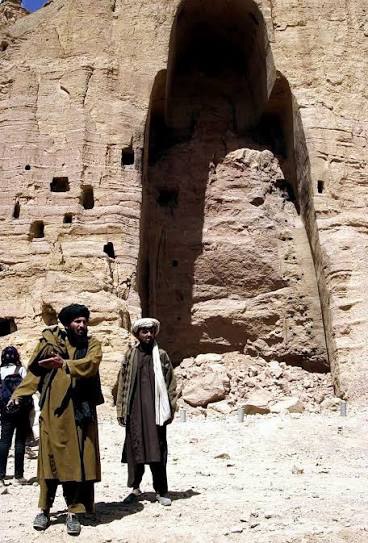

If wartime damage often occurs under the cloak of strategic necessity, the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan was a more nakedly ideological act. In March 2001, the Taliban regime deliberately dynamited two colossal sixth-century statues that had stood for over fourteen centuries in the Bamiyan valley. These statues were not merely religious icons; they were testimonies to Afghanistan’s historical role as a crossroads of civilizations along the Silk Road. The Taliban justified their destruction in the language of religious orthodoxy, claiming that the statues represented idolatry. Yet the ideological logic behind the act was unmistakable: the Buddhas embodied a plural and cosmopolitan past that the regime sought to erase. By reducing them to rubble, the Taliban attempted to eliminate visible reminders of a cultural history that did not conform to their rigid ideological worldview. The destruction therefore represented not simply iconoclasm but an attempt to obliterate historical memory itself.

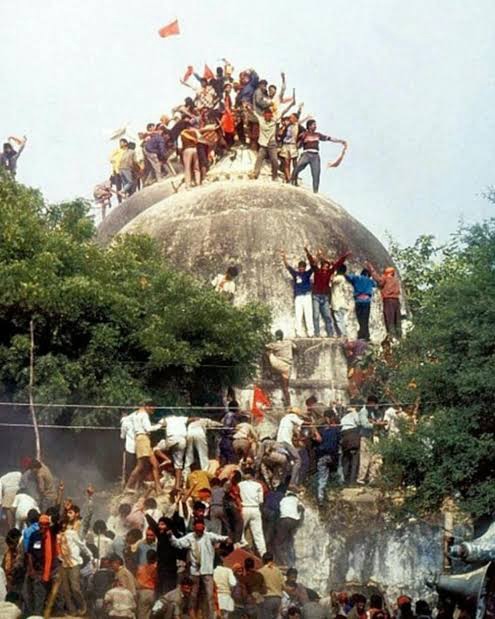

A comparable impulse to reshape the past through the destruction of monuments was visible in the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya on 6 December 1992. Built in the sixteenth century during the Mughal period, the mosque had stood for centuries as part of the architectural and historical landscape of North India. Yet in the late twentieth century it became the focal point of an aggressively mobilized political movement that sought to recast the monument as a symbol for of historical grievance. Through sustained propaganda and mass mobilization, organizations associated with the ideology of Hindutva transformed the mosque into a political target. When a mobilized crowd demolished the structure in full public view, the act was celebrated by its perpetrators as the correction of history. What was in fact destroyed, however, was not merely a mosque but a historical monument that had borne witness to centuries of cultural coexistence in the subcontinent. The demolition marked the triumph of mythologized narratives over historical scholarship and unleashed waves of communal violence that scarred the social fabric of India.

Although the contexts differ: United States-led military operations in Iran, ideological extremism in Afghanistan, and majoritarian mobilization in India, the underlying logic linking these acts of destruction is disturbingly similar. In each case, monuments become targets not because of their physical presence but because of the historical meanings they carry. Cultural heritage often embodies plural and layered pasts that resist simplistic narratives of identity. For ideological movements and militarized states alike, such complexity can be inconvenient. The destruction of monuments thus becomes a means of simplifying history, of erasing reminders of diversity, coexistence, and shared cultural inheritance.

There is also a profound hypocrisy in how such acts are justified. Those responsible frequently cloak themselves in the language of moral righteousness while committing acts that violate the most basic principles of cultural preservation. The Taliban claimed to defend religious purity while annihilating one of the world’s greatest artistic legacies. The mobs that demolished the Babri Masjid proclaimed historical justice while destroying a monument that had stood as part of India’s historical landscape for centuries. Powerful states conducting military strikes invoke strategic necessity while dismissing the damage inflicted upon historic sites as unfortunate collateral loss. In each case, rhetoric serves to mask what is fundamentally an act of cultural vandalism.

The losses inflicted by such acts are immeasurable. Monuments represent centuries of craftsmanship, artistic imagination, and collective memory. When they are destroyed, no reconstruction can restore the historical authenticity that has been lost. The Bamiyan Buddhas cannot be recreated in their original form; the Babri Masjid cannot be returned to the landscape of early modern India; and the damage inflicted upon Iranian heritage sites threatens a civilizational continuum that has endured for millennia. What disappears in such moments is not merely architecture but the tangible presence of history itself.

These episodes reveal a disturbing reality of the modern world: cultural heritage has increasingly become a battlefield upon which ideological and geopolitical struggles are waged. Instead of being protected as the shared inheritance of humanity, monuments are treated as expendable symbols within larger political agendas. The stones of Bamiyan, the ruins of Ayodhya, and the endangered heritage of Iran together remind us that the destruction of monuments is rarely accidental; it is almost always the product of deliberate human choices driven by power, ideology, or the desire to impose a singular narrative upon the past.

It is therefore imperative to condemn unequivocally all attempts to destroy cultural heritage, whether carried out in the name of religion, nationalism, or geopolitical domination. The deliberate targeting or reckless endangerment of historic monuments represents not only an attack upon a nation’s past but upon the cultural inheritance of humanity itself.

The Zionist-fascist aggression that places Iran’s historic sites in peril today must be condemned with the same moral clarity with which the world condemned the Taliban’s destruction of Bamiyan and the demolition of the Babri Masjid by the Hindutva goons. Cultural heritage belongs to all humankind, and any ideology or power that seeks to erase it stands condemned before history.

• Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi