Culture has been one of the most central and debated concepts in the social sciences, history, and anthropology, used to explain how human societies organise life, produce meaning, and transmit values across generations. At its most comprehensive level, culture refers to the socially acquired ways of life of a group of people, their beliefs, customs, norms, values, knowledge systems, institutions, artistic expressions, and everyday practices. It is not biologically inherited but learned and shared. This holistic understanding was classically articulated by EB Tylor , who defined culture as “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.” Tylor’s definition has remained influential because it captures culture as an integrated totality rather than a set of isolated traits.

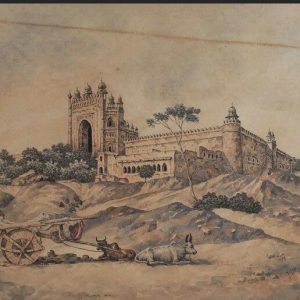

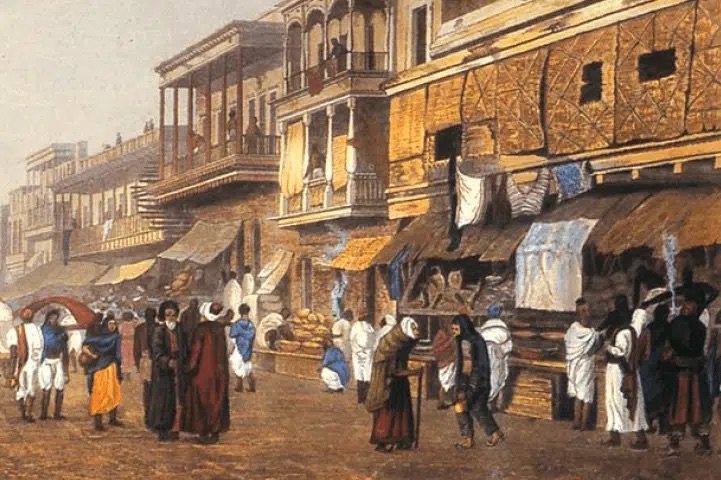

Culture manifests itself in both material and non-material forms. Material culture refers to tangible objects produced and used by human beings, ie., tools, technologies, buildings, monuments, clothing, utensils, books, machines, and works of art. Roads, dams, temples, mosques, forts, factories, railways, and digital devices all belong to this sphere. In the Indian context, historians have shown how material culture reveals patterns of production, power, and social organisation: from Harappan urban planning and Mauryan pillars to Mughal architecture and colonial infrastructure. Yet material culture is never merely physical. A monument such as the Taj Mahal is not only marble and geometry but also an expression of imperial authority, aesthetic sensibility, religious symbolism, and historical memory. Thus, material culture is always embedded in non-material meanings.

Non-material culture consists of abstract elements such as beliefs, values, norms, customs, language, symbols, emotions, and ideas. Religion, kinship, caste, moral codes, rituals, festivals, and social institutions belong to this realm. Sociologist Emili Durkheim conceptualised such shared beliefs and practices as the collective conscience, arguing that they bind individuals into a moral community and provide social cohesion. In India, this insight has been particularly useful in understanding the social role of ritual, pilgrimage, festivals, and collective religious practices, which function not only as expressions of faith but also as mechanisms of social integration.

Cultural heritage refers to those aspects of culture that societies value and consciously preserve. It may be tangible, viz. monuments, manuscripts, artefacts, historic buildings, or intangible, such as oral traditions, music, dance, rituals, festivals, local knowledge systems, and traditional skills. Indian scholars and institutions have long emphasised the importance of intangible heritage, especially in a society where much cultural transmission historically occurred through oral traditions rather than written texts. Folk songs, epics, storytelling traditions, craft knowledge, and culinary practices are crucial repositories of historical experience and social memory.

Culture is also deeply shaped by social hierarchy and power. Distinctions between elite or “high” culture and popular or folk culture reflect unequal access to education, leisure, and cultural capital. Classical music, courtly literature, and fine arts have often been associated with elites, while folk traditions, oral epics, and local rituals have been rooted in everyday life. In the Indian context, scholars such as NK Bose highlighted how popular and folk cultures are not residual or inferior forms but dynamic systems that adapt creatively to social change, often mediating between tradition and modernity.

Critical perspectives have drawn attention to the relationship between culture and material conditions. Karl Marx argued that culture forms part of the ideological superstructure shaped by economic relations. This insight was powerfully adapted to Indian history by DD Kosambi, who viewed culture as a product of historical material conditions and social formations. Kosambi demonstrated how religious forms, myths, and cultural practices in India could be historically analysed in relation to changes in modes of production, class relations, and social structure. His work marked a decisive shift away from viewing Indian culture as timeless or purely spiritual, grounding it instead in historical processes.

At the same time, interpretive approaches have emphasised culture as a system of meaning. Clifford Geertz described culture as webs of significance through which human beings make sense of the world. In the Indian context, scholars such as AK Ramanujan extended this interpretive sensitivity to folklore, oral traditions, and classical texts, showing how multiple cultural logics coexist and how meanings shift across contexts, regions, and languages. Ramanujan’s work underscored the plurality and layered nature of Indian culture, where “many pasts” and “many traditions” operate simultaneously.

A key analytical distinction in sociological thought is between ideal culture and real culture. Ideal culture consists of norms, values, and ideals that a society holds up as goals, articulated in religious doctrines, moral codes, constitutions, and textbooks. Real culture refers to actual practices in everyday life. In India, this distinction has been particularly useful in understanding religion and social reform. Sociologist MN Srinivas, through concepts such as Sanskritisation and dominant caste, showed how ideals derived from textual or elite traditions are selectively adopted, adapted, or negotiated in lived social practice. The gap between ideal prescriptions and social realities thus becomes a key site for historical and sociological analysis.

Culture in India has also been examined historically through its long-term continuities and transformations. Historian Romila Thapar has emphasised that Indian culture cannot be understood as a monolithic or unchanging entity. Instead, it has been shaped by historical interactions, debates, contestations, and reinterpretations—whether in religious traditions, political ideologies, or social institutions. Similarly, Irfan Habib has drawn attention to the material and social bases of cultural forms, linking intellectual and cultural developments to agrarian structures, state formation, and class relations.

When applied to India, therefore, culture cannot be reduced to a single set of values or practices. Indian culture represents a vast, plural, and evolving civilisational continuum shaped by regional diversity, linguistic plurality, religious traditions, and historical encounters. From Kashmir to Kanyakumari and from Kutch to Arunachal Pradesh, each region and community articulates culture differently through food habits, dress, rituals, festivals, art forms, and social norms. Culture here is best understood not as a fixed essence but as a historically produced and continuously negotiated way of life.

Culture is not merely a list of customs that people consciously follow. It is deeply internalised through socialisation from birth and shapes modes of thinking, perception, and emotional response. This is why cultural dispositions often persist even when people migrate or live outside their place of origin. Ultimately, culture operates at two interrelated levels: the level of everyday lived practices that give continuity to social life, and the level of higher cultural achievements like art, literature, philosophy, science, and architecture, that reflect a society’s intellectual and creative capacities. Together, these dimensions make culture a living, dynamic system through which human societies, including India’s richly diverse society, understand themselves and the world around them.

Indian historians working within a materialist and social-historical framework, most notably RS Sharma,BNS Yadav, and DN Jha, have argued that the emergence and consolidation of feudal social relations in early-medieval India (c. 600–1200 CE) brought about deep and long-lasting transformations in Indian culture. These changes were not merely political or economic but penetrated religious life, social organisation, ideology, and everyday cultural practices.

Central to their interpretation is the argument that the growth of land grants to brahmanas, temples, and secular intermediaries fundamentally altered the material basis of society. As land revenue was increasingly alienated from the peasantry and transferred to feudatories, villages became more self-sufficient, markets declined in many regions, and social relations grew more localised and hierarchical. This economic decentralisation produced what R. S. Sharma described as a “ruralisation” of Indian society, and this shift had significant cultural consequences.

One of the most visible cultural changes was the enhancement of brahmanical ideology and ritual dominance. As land grants endowed brahmanas with economic power, they also strengthened the authority of Sanskritic norms, ritual practices, and textual traditions. Sharma and D. N. Jha both emphasised that this period witnessed the consolidation of caste hierarchies, the sharpening of social inequalities, and the increased marginalisation of lower castes and untouchable groups. Cultural practices increasingly reflected graded inequality: access to education, religious knowledge, and prestigious rituals became more restricted, while ideas of purity and pollution were more rigidly enforced.

Feudalism also reshaped religious culture. The decline of urban centres and long-distance trade reduced the social base of heterodox traditions such as Buddhism and Jainism in many regions. In their place, Puranic Hinduism, devotional cults, and temple-centred worship expanded. Sharma argued that temples functioned not only as religious centres but also as economic and cultural institutions, controlling land, labour, and surplus. Temple rituals, festivals, and myths reinforced feudal values such as loyalty, hierarchy, and divine sanction of social order. Kings were increasingly portrayed as divinely ordained protectors of dharma, mirroring the hierarchical relations of feudal society.

Another major cultural transformation lay in the shift from a relatively open, urban-based culture to a more closed, localised village culture. B. N. S. Yadav, in particular, stressed that early-medieval culture became regionally segmented. With weakened inter-regional exchange, cultural life became more dependent on local elites and landed intermediaries. This encouraged the growth of regional languages and literatures, even as Sanskrit retained its prestige as the language of authority and sacred knowledge. Thus, feudalism simultaneously strengthened classical Sanskritic culture and fostered vernacular traditions tied to local power structures.

Feudal social relations also influenced intellectual and literary culture. Sharma and D. N. Jha both noted a relative decline in scientific and rational traditions that had flourished in earlier periods, accompanied by a greater emphasis on religious texts, commentaries, genealogies, and mytho-historical narratives. The composition of Puranas, dynastic chronicles, and religious commentaries reflected the cultural needs of a feudal society: legitimising land rights, lineage claims, and social privileges. Knowledge became more conservative and repetitive, often reinforcing existing hierarchies rather than questioning them.

Cultural attitudes towards labour and production also changed. In earlier periods, artisans and traders had occupied an important place in urban culture. Under feudalism, as Sharma argued, manual labour was increasingly devalued in ideological terms, even though it remained central to production. The cultural prestige of the peasantry and artisans declined, while rent-receiving elites, the brahmanas, landlords, and feudatories, were elevated. This ideological devaluation of labour found expression in texts that glorified land ownership and ritual status rather than productive work.

D. N. Jha further pointed out that feudal culture reinforced patriarchal norms. Women’s roles became more tightly regulated, especially within elite households, and practices such as child marriage and restrictions on women’s mobility gained stronger ideological support. Cultural ideals increasingly emphasised female chastity, obedience, and domesticity, reflecting the concerns of landed, lineage-based elites anxious about inheritance and social control.

Taken together, the works of Sharma, Yadav, and Jha suggest that Indian feudalism produced a culture marked by hierarchy, localisation, ritualism, and ideological conservatism. Culture during this period increasingly served to legitimise unequal social relations, sanctify land control, and naturalise caste and gender hierarchies. At the same time, it also generated rich regional traditions, devotional practices, and vernacular literatures that would shape Indian culture for centuries to come. Thus, feudalism did not simply arrest cultural development; it restructured culture in accordance with new material and social realities, leaving a deep imprint on the subcontinent’s historical trajectory.

• Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi