Dara Shukoh occupies a singular and paradoxical position in Mughal history. He has attracted a remarkably diverse historiography, shaped as much by historians’ intellectual predispositions as by the politically mediated nature of Mughal sources. Early colonial and nationalist writers, most notably Sir Jadunath Sarkar, framed Dara through a stark moral opposition with Aurangzeb, portraying him as a tolerant, humanistic, almost proto-secular prince tragically eliminated by religious orthodoxy. This binary, though influential, flattened the political realities of Mughal succession and transformed Dara into a symbolic counter-figure rather than a historically situated actor. A crucial corrective was offered by Kalika Ranjan Qanungo, who rejected romanticisation and insisted on judging Dara as a political figure. Qanungo acknowledged Dara’s intellectual sincerity and cultural brilliance but emphasised his lack of administrative training, military competence, and political tact. For him, Dara’s failure stemmed not from religious heterodoxy but from an inability to convert cultural authority into political power. Later scholarship, especially that of M Athar Ali, shifted attention to the structural logic of Mughal politics—factional alignments, noble interests, command over resources—rather than personal belief. More recent cultural-intellectual studies by Supriya Gandhi have further nuanced this picture by situating Dara within Mughal traditions of knowledge production, translation, spiritual kingship, and elite piety. Taken together, these approaches move us away from moral binaries and toward an understanding of Dara Shukoh as a historically grounded prince whose intellectual ambitions collided with the unforgiving constraints of early modern imperial power.

As the eldest son and acknowledged heir-apparent of Emperor Shahjahan, Dara enjoyed unparalleled paternal favour. Yet this intimacy proved politically debilitating. Though appointed subahdar of Punjab and Allahabad, he governed these provinces largely through deputies and remained mostly at court, thereby missing the sustained provincial and military apprenticeship traditionally expected of Mughal princes. Qanungo was particularly sharp on this point: Dara, shielded from adversity, never acquired the discipline of command or the capacity to negotiate power under pressure. Unlike Aurangzeb, whose long tenures in the Deccan forged military authority and noble alliances, Dara remained dependent on imperial favour rather than personal networks. Temperamentally reflective and intellectually inclined, he was ill-suited to the aggressive calculus of succession politics. Compounding this was an arrogance born of privilege; Dara repeatedly alienated senior nobles such as Mirza Raja Jai Singh, Shaista Khan, and Khalilullah Khan by humiliating them and disregarding courtly norms. For example, he would derogatorily call Jai Singh as “Dakhini Bandar”. In a polity where kingship depended on managing egos and forging consensus among elites, such behaviour proved fatal.

In stark contrast to these political limitations stood the coherence and ambition of Dara’s intellectual and spiritual vision. His intellectual world was anchored in Qadiri Sufism. Introduced by Shah Jahan to the celebrated mystic Miyan Mir, Dara later became a devoted disciple of Mulla Shah Badakhshi. While Sufi devotion was not uncommon in the Mughal household—Jahanara Begum shared similar inclinations—Dara alone sought to systematise and textualise mystical experience. His works, including Safinat-ul-Auliya and Sakinat-ul-Auliya, compiled hagiographical and doctrinal material on Sufi saints and traced chains of spiritual authority; Risala-i Haqqnuma explored metaphysical truth and ethical conduct; and Hasanat-ul-Arifin assembled aphoristic sayings of Sufi masters. These were serious intellectual interventions, not ornamental exercises in piety. Yet, as Qanungo perceptively observed, Dara confused spiritual authority with political legitimacy, assuming that metaphysical depth could compensate for deficiencies in administration and military command.

This intellectual ambition reached its most original expression in Dara’s comparative theological works, above all Majmaʿ-ul-Baḥrain (“The Confluence of the Two Seas”). Far from being a plea for vague tolerance, the text is a sustained metaphysical argument that Sufi notions of divine unity (tawḥīd) and Vedantic concepts of ultimate reality (brahman) converge at a deeper, esoteric level. Dara approached Hinduism not as a collection of popular rituals but as a philosophical tradition whose highest articulation lay in the Upanishads. He consistently distinguished between external religious forms and inner truth, arguing that conflict arose when surface practices were mistaken for ultimate meaning. His engagement with Hinduism was thus elite, text-centred, and philosophical rather than devotional or populist. Importantly, Majmaʿ-ul-Baḥrain did not advocate the fusion of religions; it sought instead to reveal a shared mystical grammar underlying distinct traditions.

This vision culminated in Dara’s Persian translation of the Upanishads, titled Sirr-i Akbar (“The Greatest Secret”). In the introduction, Dara advanced his most daring claim: that the Qur’anic Kitab al-Maknun, the “Hidden Book,” referred to in Islamic scripture, was none other than the Upanishads. To Dara, these texts contained the primordial articulation of monotheism, later reaffirmed and clarified by Islam. The project was explicitly pedagogical and imperial. By translating the Upanishads into Persian, Dara sought to make them accessible to Muslim scholars and integrate Indian metaphysics into the Persianate intellectual world of the Mughal elite. As Supriya Gandhi has shown, translation in the Mughal context functioned as a mode of sovereignty, a way of claiming India’s intellectual past and embedding Mughal authority more deeply in the subcontinent.

Dara’s pluralism must be distinguished carefully from Akbar’s doctrine of ṣulḥ-i kul. Akbar’s ṣulḥ-i kul was primarily political and administrative, a principle of universal peace designed to stabilise empire and secure loyalty across religious communities. Dara’s version, by contrast, was metaphysical and intellectual. It did not emerge from the necessities of governance but from a conviction that all true religions shared a single esoteric core. Where Akbar tolerated difference to rule effectively, Dara sought to interpret difference away at the level of ultimate truth. Further, Akbar’s sulh e kul was a rejection of religion, Dara’s sulh e kul was belief that there is truth in all religions. This distinction is crucial, for it reveals why Dara’s vision, however sophisticated, lacked the institutional mechanisms that made Akbar’s policy durable.

Dara’s conception of sovereignty extended beyond texts into culture, art, and architecture. He was a passionate patron of music, painting, and calligraphy, arts viewed with suspicion by Aurangzeb. The celebrated Dara Shukoh Album, presented to his wife Nadira Banu Begum, reveals him not merely as a patron but as an aesthete of remarkable sophistication; its later defacement and anonymisation after his execution mirror his systematic erasure from official memory.

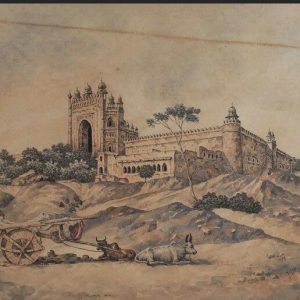

Architecturally, Dara commissioned the tomb of Nadira Banu in Lahore, the shrine of Miyan Mir, the Dara Shukoh Library in Delhi, the Akhun Mulla Shah Mosque, and the Pari Mahal complex in Srinagar—structures that embody a synthesis of Persianate form, local traditions, and spiritual symbolism, reflecting his belief that architecture could serve as a medium of ethical and metaphysical expression.

Contrary to later assumptions, Dara’s engagement with Hindu, Sufi, and even Jesuit traditions was not exceptional within Mughal practice. Akbar, Jahangir, and Shah Jahan had all patronised non-Islamic scholars and ascetics. Qanungo was emphatic that religion was not the decisive factor in Dara’s downfall; the charge of kufr functioned largely as a post-facto political justification. What doomed Dara was his failure to command armies, build durable noble alliances, and inspire confidence in moments of crisis. Aurangzeb’s subsequent erasure of Dara from chronicles and the uncertainty surrounding his burial site underscore the politics of memory, yet even Aurangzeb complicates the stereotype of sectarian vengeance by arranging marriages between his children and Dara’s descendants and maintaining certain Sufi affiliations himself.

Dara Shukoh thus represents not a martyr to tolerance but a failed experiment in metaphysical kingship. He imagined a Mughal sovereignty grounded in spiritual insight, philosophical synthesis, and cultural refinement. As Qanungo perceptively argued, such ideals could enrich empire but could not sustain it. In a polity where authority rested on military command, revenue extraction, and elite consensus, Dara’s intellectual capital proved insufficient. His enduring significance lies not in what he ruled, but in what he attempted to imagine: an empire in which Islam and Hinduism were not merely accommodated but philosophically reconciled. That this vision failed tells us less about its nobility than about the unforgiving logic of early modern imperial power.

• Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi