The historical relationship between India and Afghanistan must be approached as a history of shared spaces rather than of bounded territories. Long before the emergence of modern political borders, Afghanistan functioned as India’s principal north-western gateway, linking the subcontinent with Central Asia, Iran, and the Mediterranean world. The Hindu Kush was never an absolute barrier; instead, its passes—Khyber, Bolan, and Gomal—structured movement and exchange. Ancient Indian geographical imagination conceptualised this zone as part of the Uttarāpatha, the northern route of commerce and communication, suggesting a spatial order defined by circulation rather than enclosure.

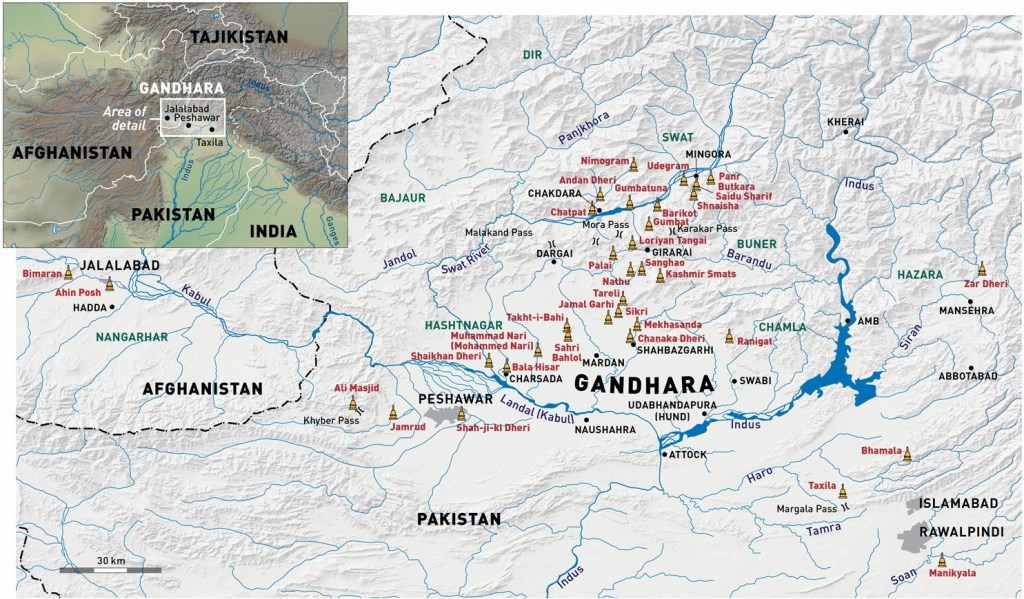

This connectivity was already firmly in place in the ancient period. Regions corresponding to present-day eastern Afghanistan and north-western Pakistan—above all Gandhāra—were deeply embedded in the political and cultural world of early India. Gandhāra, with centres such as Taxila, functioned as a major intellectual and commercial hub, where Vedic, Buddhist, Iranian, and Hellenistic traditions intersected. The incorporation of Afghanistan into the Mauryan Empire in the third century BCE marked a decisive moment in this shared history. Ashokan inscriptions discovered at Kandahar, composed in Greek and Aramaic, reveal both the reach of imperial authority and the cosmopolitan character of the Indo-Afghan region. These inscriptions also indicate that Afghanistan lay at the crossroads of multiple cultural worlds, rather than on the margins of any one of them.

In the centuries following the Mauryas, the Indo-Afghan space became a crucial segment of the trans-Asian trading network conventionally described as the Silk Road. While often imagined as a single route, the Silk Road consisted of multiple, intersecting corridors, many of which passed through Afghanistan, linking India to Bactria, Sogdiana, China, and the Iranian plateau. Afghan cities such as Balkh, Bamiyan, and Kapisa emerged as nodal points where Indian merchants, Central Asian traders, and itinerant monks converged. Through these routes flowed not only silk and spices, but also ideas, artistic forms, technologies, and religious traditions.

The Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian, and Kushan polities ruled across Afghanistan and north India as a single political and economic continuum, reinforcing these connections. Under the Kushans in particular, Afghanistan occupied a central place in a vast empire that stretched from the Gangetic plains to Central Asia. Buddhist monasteries along the Silk Road—most famously at Bamiyan—were sustained by Indian patronage and merchant wealth, and they played a decisive role in transmitting Buddhism from India into Central Asia and China. As scholars such as Romila Thapar have noted, these developments challenge later civilisational boundaries by revealing an ancient world in which Afghanistan was integral to India’s religious and commercial life.

These ancient patterns of movement and exchange laid the groundwork for the medieval and early modern Indo-Afghan relationship. Dynasties that later ruled India—the Ghaznavids, Ghurids, and Timurids—emerged from Afghan and Trans-Oxanian contexts already shaped by centuries of interaction with the subcontinent. The Indo-Persian political culture that developed from the thirteenth century onwards drew upon this inherited geography of routes, markets, and shared cultural idioms. Historians such as Irfan Habib and Muzaffar Alam have emphasised that the political vocabulary and administrative practices of medieval India cannot be understood without recognising Afghanistan’s role as a connective zone rather than a point of rupture.

This longue durée of integration reached its most structured and explicit form under the Mughal Empire. The Mughal state itself was born out of the Indo-Afghan corridor, and Afghanistan lay at the heart of its political geography. For Babur, Kabul was his watan, a homeland that anchored his claims to legitimacy and sovereignty.

The medieval and early modern periods intensified these connections, culminating in the Mughal era, when Afghanistan assumed a position of extraordinary centrality in the political imagination and administrative structure of the Indian empire. The Mughal state itself was born out of the Indo-Afghan corridor. As pointed out above, Kabul was not a frontier possession but Babur’s watan, imbued with emotional, strategic, and cultural significance. Babur’s repeated oscillation between Kabul and Hindustan, described vividly in the Baburnama, reveals a political geography in which the Hindu Kush did not divide worlds but linked them. Kabul functioned as the hinge between Central Asian Timurid traditions and the Indian environment into which Babur inserted himself after 1526.

Under his successor Humayun too, control over Afghanistan, particularly Kabul and Qandahar, was essential to Mughal survival. The Afghan zone provided not only military manpower but also legitimacy rooted in Timurid and Chinggisid traditions. Humayun’s exile in Iran and subsequent return to India via Qandahar and Kabul further reinforced the role of Afghanistan as a political bridge rather than a periphery. Stephen Dale and Ali Anooshahr have convincingly shown that early Mughal sovereignty was transregional in character, resting on the ability to mobilise resources and loyalties across Central Asia, Afghanistan, and northern India.

This pattern continued and stabilised under Akbar. Kabul was incorporated as a suba within the Mughal administrative system, its governors often drawn from the highest ranks of the nobility. Far from being marginal, the province occupied a privileged position in the imperial hierarchy, frequently assigned to princes or trusted grandees. Akbar’s policy towards Afghan tribes was not merely coercive but integrative; Afghan nobles were absorbed into the mansabdari system and deployed across the empire. Iqtidar Alam Khan and M Athar Ali’s works on Mughal nobility demonstrate the extent to which Afghans remained a vital component of the imperial elite well into the seventeenth century.

Under the early Mughal rulers, the transregional sovereignty was institutionalised. Kabul not only became a Mughal suba, but was frequently entrusted to princes or senior nobles, reflecting its privileged status within the imperial order. Control over Kabul and Qandahar was vital not merely for defence but for maintaining access to the wider Central Asian world. The long contest with the Safavids over Qandahar underscores how deeply Mughal India remained embedded in an Indo-Afghan-Iranian geopolitical system. These struggles were accompanied by sustained diplomatic and cultural exchange, reinforcing a shared political culture across the region.

Social and economic ties further bound Mughal India and Afghanistan together. Afghan merchants operated extensively in Indian cities, while Indian traders from Punjab and Multan were active across Afghan markets, continuing commercial patterns that can be traced back to ancient Silk Road exchanges. Afghan soldiers, scholars, and Sufi figures circulated freely within the empire, sustaining what Richard Eaton and Nile Green have described as a mobile Indo-Persian cultural sphere. Afghanistan thus remained integral to the everyday functioning of Mughal India, not merely to its frontier defence.

The strategic importance of Afghanistan lay not only in its manpower but also in its role as the empire’s first line of defence against Central Asian and Iranian powers. The long contest with the Safavids over Qandahar illustrates this clearly. For the Mughals, Qandahar was less a distant fortress than a keystone of imperial security, linking Kabul to the Indus plains. The repeated transfer of Qandahar between the Mughals and Safavids during the seventeenth century underscores how deeply the city was embedded in the geopolitics of both India and Iran. Muzaffar Alam has shown that these conflicts were accompanied by intense diplomatic exchanges and cultural negotiations, further binding the Indo-Afghan-Iranian world.

Economically and socially, Mughal India and Afghanistan were closely intertwined. Afghan merchants operated extensively in Indian cities such as Lahore, Delhi, Agra, and Burhanpur, while Indian traders—particularly from Punjab and Multan—maintained commercial networks in Kabul and beyond. Afghan soldiers, clerics, and Sufis circulated freely across the empire, contributing to what Richard Eaton and Nile Green have described as a shared Indo-Persian cultural sphere. Afghanistan thus remained integral to the everyday functioning of Mughal India, not merely to its high politics.

The later Mughal period did not sever these ties, even as imperial authority weakened. On the contrary, Afghanistan re-emerged as a decisive force in Indian politics in the eighteenth century. The invasion of India by Nadir Shah in 1739, culminating in the sack of Delhi, dramatically exposed the fragility of Mughal power. Yet Nadir Shah’s march into India followed long-established routes through Afghanistan, routes that had historically bound the two regions together. His intervention was not an aberration but a reminder of Afghanistan’s enduring role as the north-western axis of Indian politics.

In the aftermath of Nadir Shah’s death, his Afghan general Ahmad Shah Abdali—also known as Ahmad Shah Durrani—carried this legacy forward. Abdali’s repeated invasions of India, including the decisive Battle of Panipat in 1761, were not merely acts of external aggression but the assertion of a political order that once again spanned Afghanistan and northern India. The Durrani Empire, with its base in Kandahar and Kabul and its reach into Punjab and Delhi, echoed earlier patterns of Indo-Afghan imperial integration. As recent scholarship has noted, Abdali operated within a political culture familiar to Mughal elites, drawing upon shared norms of kingship, military organisation, and revenue extraction.

The Mughal period thus reveals the Indo-Afghan relationship at its most intimate and complex. Afghanistan was simultaneously homeland, province, military reservoir, and strategic buffer for the Mughal Empire. Its cities and passes structured the rhythms of imperial expansion, defence, and collapse. The later colonial transformation of this region into a rigid frontier, culminating in the Durand Line in 1893, represents a sharp rupture from this older history of fluidity and interdependence.

In conclusion, the Mughal experience compels us to rethink India–Afghanistan relations beyond the language of invasion or foreignness. From Babur’s Kabul to Abdali’s Panipat, Afghanistan was not outside Indian history but one of its constitutive spaces. Recovering this shared past allows us to see the Indo-Afghan world as a connected historical zone, fractured only recently by colonial boundary-making and modern geopolitics, and invites a reassessment of South Asia’s place within wider Eurasian historical processes.

• Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi