“Do not show the face of Islam to others; instead, show your face as the follower of true Islam.”

— Sir Syed Ahmad Khan

Born on 17 October 1817 in Delhi, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan emerged as one of the most remarkable figures of 19th-century India — a philosopher, social reformer, historian, and educator whose vision shaped modern Indian Muslim identity. Deeply devoted to the cause of education, he believed that only widespread, modern learning could enlighten and empower the masses.

A devout Muslim, yet deeply troubled by orthodoxy, Sir Syed’s reformist zeal found expression in his modernist commentary on the Qur’an and a sympathetic interpretation of the Bible, both seeking harmony between revelation and reason. His intellectual temperament was rational and inclusive, shaped by both Islamic theology and Enlightenment humanism.

He established schools at Moradabad (1858) and Ghazipur (1863), founded the Scientific Society (Aligarh, 1864) to translate Western works into Indian languages, and launched the periodical Tehzīb-ul-Akhlāq (1870) to reform social and moral attitudes. The culmination of his lifelong mission was the foundation of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College (MAO College) on 7 January 1877, patterned after Oxford and Cambridge which would eventually evolve into Aligarh Muslim University.

Sir Syed and the Colonial Moment

Sir Syed’s long association with the East India Company placed him in a complex position during the Revolt of 1857. Witnessing the devastation of Delhi and the collapse of Mughal institutions, he sought to diagnose the roots of the tragedy. In his path-breaking work Asbāb-i Baghāwat-i Hind (The Causes of the Indian Revolt, 1859), he held the British government itself responsible, citing its aggressive expansionism, racial arrogance, and ignorance of Indian traditions.

He followed it with Tārīkh-i Sarkashī-i Bijnor, a detailed local account of the revolt. These works marked Sir Syed as an early historian of modern India, who analyzed events through empirical observation and social reasoning, not blind loyalty.

Though often called a British loyalist, and later associated with the formation of the Muslim League to safeguard community interests, he was doubly misunderstood.

The orthodox clergy denounced him as a “Natury Jogi,” a follower of Darwin and a denier of the Qur’an. The British establishment distrusted him as a critic who exposed their administrative failures.

Yet, beyond these misreadings stood a man envisioning a revived Indian Muslim community, equipped with both the ethical strength of Islam and the scientific temper of the West.

The Historian and Archaeologist

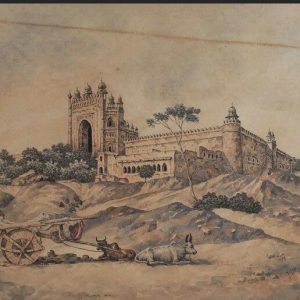

Few realize that Sir Syed Ahmad Khan was not only a reformer but also one of India’s first historical archaeologists. His monumental work Āthār-ul-Ṣanādīd (1847; revised 1854), literally “Monuments of the Nobles”, was the earliest survey of Delhi’s monuments written in Urdu and Persian.

In this text, he meticulously documented mosques, tombs, gardens, and madrasas, recording measurements, architectural details, and inscriptions with the precision of a modern archaeologist. It remains, even today, an indispensable primary source for the study of Delhi’s medieval architecture.

In 1847, the Delhi Archaeological Society was established, and Sir Syed became an active member. In its journal, he published a path-breaking article on the ancient bricks of Hastinapur, identifying strata and typologies that prefigured later archaeological methods. The only comparable study came decades later from Sir John Marshall, Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India.

Sir Syed’s approach was holistic. He copied inscriptions in languages he did not know, including Prakrit, out of sheer respect for historical record. His attention to epigraphy, architecture, and urban morphology marks him as a genuine pioneer of historical archaeology in India.

The Aligarh Legacy and Archaeological Tradition

Sir Syed’s intellectual curiosity extended into his institutional creation at Aligarh. During his residence there, he collected antiquities, sculptures, and architectural fragments from neighboring regions, which were displayed in the Department of History and later preserved in the Central University Museum.

This collection catalogued by Professor R. C. Gaur, includes stone sculptures, door jambs, and ornamental fragments, embodying the founder’s passion for preserving the material past.

The Department of History, following his tradition, developed a robust Archaeology Section, which became one of the premier centers of field archaeology in India. Its excavations at Atranji Khera, Jhakera, Lal Qila, Fathpur Sikri, and along Mughal highways stand as enduring tributes to the legacy of Sir Syed whose integration of history, archaeology, and education gave Aligarh its distinct identity as both a seat of learning and a guardian of heritage.

Connoisseur of Composite Culture

Sir Syed’s appreciation of heritage went beyond monuments and manuscripts. He was, above all, a connoisseur of India’s composite culture, its interwoven Hindu-Muslim traditions, its shared languages, and its syncretic arts. His friendships with Hindu scholars such as Raja Jai Kishan Das, his use of Urdu as a cultural bridge, and his assertion that “Hindus and Muslims are the two eyes of the same beautiful bride of India” reflect his belief in the essential unity of the subcontinent.

The British decision in 1842 to replace Persian with English in administration had deeply alarmed Indian Muslims, but Sir Syed’s response was constructive, not reactionary. He urged the community to master English and Western sciences so as to remain socially and politically relevant. His educational reforms thus became acts of cultural preservation through adaptation and a renewal of heritage, not its abandonment.

The Context of His Nationalism

It is important to remember that Sir Syed lived in an age before the modern concept of “nationhood.” Terms like watan and qaum were fluid and contextual, denoting a people, region, or community. Sir Syed’s vision of a qaum was civilizational rather than territorial.

He was no Jamaluddin Afghani, nor a pan-Islamist agitator. His reforms were firmly rooted south of the Himalayas in the soil of India. His dream was of an enlightened Indian Muslim community, loyal to its faith yet integrated with the progress of its homeland.

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan stands today as one of the earliest interpreters of India’s national heritage, a man who combined the scholar’s precision, the reformer’s courage, and the patriot’s faith in the civilizational unity of India.

His Āthār-ul-Ṣanādīd illuminated the architectural past; his Asbāb-i Baghāwat-i Hind explained the political crises of his present; his Scientific Society, Tehzīb-ul-Akhlāq, and MAO College prepared the ground for an enlightened future.

In celebrating him, we celebrate the enduring belief that education and heritage are twin pillars of national regeneration. To walk through the gates of Aligarh today past the Victoria Gate, Strachey Hall, and the Sir Syed University Museum (now known as Musa Dakri Museum) is to retrace the vision of a man who sought to unite the reason of the modern age with the wisdom of our collective past.

Sir Syed Ahmad Khan was, and remains, a true connoisseur of our national heritage.

• Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi