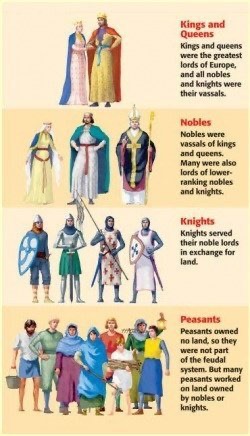

The first assimilation of ‘feudalism’ in the Indian context occurred at the hands of Col. James Tod, the celebrated compiler of the annals of Rajasthan’s history in the early part of the nineteenth century, For Tod, as for most European historians of his time in Europe, lord-vassal relationship constituted the core of feudalism. The lord in medieval Europe looked after the security and subsistence of his vassals and they its Continuities in turn rendered military and other services to the lord. A sense of loyalty also tied the vassal to the lord in perpetuity. Tod found the institution and the pattern replicated in the Rajasthan of his day in good measure.

The term feudalism continued to be viewed, off and on, in works of history in India, often with rather vague meanings attached to it. It was with the growing Marxist influence on Indian history writings between the mid-1950s and the mid-60s that the term came to be disassociated from its moorings in lord-vassal relationship and acquired an economic meaning, or rather a meaning in the context of the evolution of Indian class structure. One of the major imperatives of the formulation of an Indian feudalism was, paradoxically, the dissatisfaction of Marxist historians with Marx’s own placement of pre-colonial Indian history in the category of the Asiatic Mode of Production. Even though Marx had created this category himself, much of the substance that had gone into its making was commonplace among Western thinkers of the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries.

Marx had perceived the Asiatic Mode of Production as an ‘exception’ to the general dynamic of history through the medium of class struggle. In Asia, he, along with numerous other thinkers, assumed there were no classes because all property belonged either to the king or to the community; hence there was no class struggle and no change over time. He shared this notion of the changeless Orient with such eminent thinkers as Baron de Montesquieu, James Mill, Friedrich Hegel and others. Real dynamism, according to them, came only with the establishment of colonial regimes which brought concepts and ideas of change from Europe to the Orient. Indian Marxist historians of the 1950s and 60s were unwilling to accept that such a large chunk of humanity as India, or indeed the whole ofAsia, should remain changeless over such large segments of time. They expressed their dissatisfaction with the notion of the Asiatic Mode of Production early on. In its place some of them adopted the concept of feudalism and applied it to India. Irfan Habib, the leading Marxist historian of the period, however, put on record his distance from ‘Indian feudalism’ even as he vehemently criticised the Asiatic Mode of Production.

D. D. Kosambi gave feudalism a significant place in the context of socio-economic history. He conceptualised the growth of feudalism in Indian history as a two-way process: from above and from below in his landmark book, An Introduction to the Study of Indian History, first published in 1956. From above the feudal structure was created by the state granting land and rights to officials and Brahmins; from below many individuals and small groups rose from the village levels of power to become landlords and vassals of the kings.

Kosambi, in his characteristic mode, formulated the notion of feudalism in the shape of a formula rather than in a detailed empirical study. This major task was taken up by Professor R. S. Sharma in his Indian Feudalism, 1965. However, R. S. Sharma did not follow the Kosambian formula of feudalism from below and from above; instead, he envisioned the rise of feudalism in Indian history entirely as ‘the consequence of state action, i.e. from above. It was only later that he turned his attention to the other phenomenon.

R. S. Sharma essentially emulated the model of the rise and decline of feudalism in Europe formulated in great detail by the Belgian historian of the 1920s and 3Os, Henri Pirenne. Pirenne had displaced the dominant stereotype of European feudalism as lord-vassal relationship and substituted in its place one that had much wider and deeper range of consequences for society. He postulated that ‘grand trade’, i.e long distance trade in Europe across the Mediterranean, had allowed European economy, society and civilisation to flourish in Antiquity until its disruption by the Arab invasions of Europe in the seventh century. Disruption of trade led to the economy’s ‘ruralisation’, which made it inward, rather than outward looking. It also resulted in what Pirenne called ‘the closed estate economy’. The closed estate signified the unit of land held as estate by the lord [10,000 acres on an average] and cultivated by the peasant, where trade was minimal and almost everything the inhabitants of the estate required was produced within. These estates, in other words, were economically ‘self-sufficient’ units. The picture changed again from the eleventh century when the Crusades threw the Arabs back to the Near East; this led to the revival of trade and cities and the decline of feudalism. Pirenne thus posited an irreconcilable opposition between trade and urbanisation on one hand and feudalism on the other.

R S Sharma copied this model in almost every detail, often including its terminology, on to the Indian historical landscape. He visualised the decline of India’s long distance trade with various parts of the world after the fall of the Guptas; urbanisation also suffered in consequence, resulting in the economy’s ruralisation. A scenario thus arose in which economic resources were not scarce but currency was. Since coins were not available, the state started handing out land in payment to its employees and grantees like the Brahmins. Along with land; the state also gave away more and more rights over the cultivating peasants to this new class of ‘intermediaries’. The increasing subjection of the peasants to the intermediaries reduced them to the level of serfs, their counterparts in medieval Europe. The rise of the class of intermediaries through the state action of giving grants to them is the crucial element in R S Sharma’s construction of Indian feudalism. Later on in his writings, he built other edifices too upon this structure, like the growth of the class of scribes, to be consolidated into the caste of Kayasthas, because state grants needed to be recorded. The crucial process of land grants to intermediaries lasted until about the eleventh century when the revival of trade reopened the process of urbanisation. The decline of feudalism is suggested in this revival, although R S Sharma does not go into this aspect in as much detail. The one element that was missing in this picture was the Indian counterpart of the Arab invasion of Europe; however, Professor B N S Yadava, another eminent proponent of the Indian feudalism thesis, drew attention to the Hun invasions of India which almost coincided with the beginning of the rise of feudalism here. The oppressive feudal system in Europe had resulted in massive rebellions of the peasantry in Europe; in India R S Sharma looked for evidence of similar uprising but found only one example of Kaivartas – who were essentially boatmen in eastern Bengal but also engaged part time in cultivation – having revolted in the eleventh century.

The thesis propounded in its fully-fledged form in 1965 has had a great deal of influence on subsequent history writing on the period in India. Other scholars supported the thesis with some more details on one point or another, although practically no one explored any other aspect of the theme of feudalism, such as social or cultural aspect for long afterwards. B N S Yadava and D N Jha stood firmly by the feudalism thesis. The theme found echoes in south Indian historiography too, with highly acclaimed historians like MGS Narayanan and Noburu Karashima abiding by it. There was criticism too in some extremely learned quarters; the most eminent among critics was D C Sircar. There was too a fairly clear ideological divide which characterised history writing in India in the 1960s and 70s: D D Kosarnbi, R S Sharma, B N S Yadava and D N Jha were firmly committed Marxists; D C Sircat stood on the other side of the Marxist fence. However, neither support nor opposition to the notion of feudalism opened up the notion’s basic structure to further exploration until the end of the 1970s. The opening up came from within the Marxist historiographical school. We shall return to it in a little while.

In 1946 one of the most renowned Marxist economists of Cambridge university, UK, Maurice Dobb, published his book, Studies in the Development of Capitalism in which he first seriously questioned the Pirennean opposition between trade and feudalism and following Engels’ insights drew attention to the fact that the revival of trade in Eastern Europe had brought about the ‘second serfdom’, i.e., feudalism. He thus posited the view that feudalism did not decline even in Weskrn Europe due to the revival of trade but due to the flight of the peasants to cities from excessive and increasing exploitation by the lords in the countryside. This thesis led to an international debate in the early 1950s among Marxist economists and historians. The debate was still chiefly confined to the question whether feudalism and trade were mutually incompatible. Simultaneously, in other regions of the intellectual landscape, especially in France, where an alternative paradigm of history writing, known as the Annales paradigm, was evolving, newer questions were being asked and newer dimensions of the problem being explored. Some of these questions had travelled to India as well.

WAS THERE FEUDALISM IN INDIA?

It was thus that in 1979 a Presidential Address to the Medieval India Section of the Indian History Congress’s fortieth session was entitled ‘Was There Feudalism in Indian History?‘ Harbans Mukhia, its author, a committed practitioner of Marxist history writing, questioned the Indian feudalism thesis at the theoretical plane and then at the empirical level by comparing the medieval Indian scenario with medieval Europe.

The theoretical problem was concerned with the issue whether feudalism could at all be conceived of as a universal system. If the driving force of profit maximisation had led capitalism on to ever rising scale of production and ever expanding market until it encompassed the whole world under its dominance, something we are witnessing right before our eyes, and if this was a characteristic of capitalism to thus establish a world system under the hegemony of a single system of production, logically it would be beyond the reach of any precapitalist system to expand itself to a world scale, i.e. to turn into a world system. For, the force of consumption rather than profit maximiation drove precapitalist economic systems, and this limited their capacity for expansion beyond the local or the regional level. Feudalism thus could only be a regional system rather than a world system. The problem is hard to resolve by positing different variations of feudalism: the European, the Chinese, the Japanese and the Indian, etc., although this has often been attempted by historians. For, then either the definition of feudalism turns so loose as to become synonymous with every pre-capitalist system and therefore fails to demarcate feudalism from the others and-is thus rendered useless; or, if the definition is precise, as it should be to remain functional, the ‘variations’ become so wide as to render it useless. Indeed, evenwithin the same region, the variations are so numerous that some of the most respected historians of medieval Europe in recent years, such as Georges Duby and Jacques Le Goff, tend to avoid the use of the term feudalism altogether; so sceptical they have become of almost any definition of feudalism.

The empirical basis of the questioning of Indian feudalism in the 1979 Presidential Address lay in a comparison between the histories of medieval Western Europe and medieval India, pursued at three levels: the ecological conditions, the technology available and the social organisation of forms of labour use in agriculture in the two regions. With this intervention, the debate was no longer confined to feudalism/ trade dichotomy which in any case had been demonstrated to be questionable In its own homeland.

The empirical argument followed the perspective that the ecology of Western Europe gave it four months of sunshine in a year; all agricultural operations, from tilling the field to sowing, tending the crop, harvesting and storing therefore must be completed within this period. Besides, the technology that was used was extremely: labour intensive and productivity of both land and labour was pegged at the dismal seed-yield ratio of 1 :2.5 at the most. Consequently the demand for labour during the four months was intense. Even a day’s labour lost would cut into production. The solution was found in tying of labour to the land, or serfdom. This generated enormous tension between the lord and the serf in the very process of p-reduction; the lord would seek to control the peasant labour more intensively; the peasant would, even while appearing to be very docile, try to steal the lord’s time to cultivate his own land. The struggle, which was quiet but intense, led to technological improvement, rise in productivity to 1 :4 by the twelfth century, substantial rise in population and therefore untying of labour from land, expansion of agriculture and a spurt to trade and urbanisation. The process was, however, upset by the Black Death in 1348-51 which wiped out a quarter of the population leading to labour scarcity again. The lords sought to retud to the old structures of tied labour; the peasants, however, who had tasted better days in the 11th and 12th centuries, flew into rebellions all over Europe especially during the 14th century. These rebellions were the work of the prosperous, rather than the poor peasants. By the end of the century, feudalism had been reduced to a debris.

Indian ecology, on the other hand, was marked by almost ten months of sunshine where agricultural processes could be spread out. Because of the intense heat, followed by rainfall, the upper crust of the soil was the bed of fertility; it therefore did not require deep, labour intensive digging. The hump on the Indian bull allowed the Indian peasant tp use the bull’s drought power to the maximum, for it allowed the plough to be placed on the bull’s shoulder; the plain back on his European counterpart would let the plough slip as he pulled it. It took centuries of technological improvement to facilitate full use of the bull’s drawing power on medieval European fields. The productivity of land was also much higher in medieval India, pegged at 1 : 16. Besides, most Indian lands yielded two crops a year, something unheard of in Europe until the ninteenth century. The fundamental difference in conditions in India compared to Europc also made it imperative that the forms of labour use in agriculture should follow a different pattern. Begar, or tied labour, paid or unpaid, was seldom part of the process of production here; it was more used for non-productive purposes such as carrying the zamindar ‘s loads by the peasants on their fields or supplying milk or oil, etc. to the zamindars and jagirdars on specified occasions. In other words tension between the peasant and the zamindar or the jagirdar was played out outside the process of production on the question of the quantum of revenue.

We do not therefore witness the same levels of technolagical breakthroughs and transformation of the production processes in medieval India as we see in medieval Europe, although it must be emphasised that neither technology nor the process of agricultural production was static or unchanging in India.

The 1979 Address had characterised the medieval Indian system as one marked its Continuities by he peasant economy. Free peasant was understood as distinct from the medieval European serf. Whereas the serf’s labour for the purposes of agricultural production was set under the control of the lord, the labour of his Indian counterpart was under his own control; what was subject to the state’s control was the amount of produce of the land in the form of revenue. A crucial difference here was that the resolution of tension over the control of labour resulted in transformation of the production system from feudal to capitalist in European agriculture from the twelfih century onwards; in India tension over revenue did not affect the production system as such and its transfornation began to seep in only in the twentieth century under a different set of circumstances.

‘Was There Feudalism in Indian History?’ was reprinted in the pages of a British publication, The Journal of Peasant Studies in 198 1. Within the next few years it had created so much interest in-international circles that in 1985 a special double issue of the journal, centred on this paper, comprising eight articles from around the world and the original author’s response to the eight, was published under the title Feudalism and Non-European Societies, jointly edited by T. J. Byres of the School of Oriental and African Studies, London University, editor of the journal, and the article’s author. It was also simultaneously published as a book. The title was adopted keeping in view that the debate had spilled over the boundaries of Europe and India and had spread into China, Turkey, Arabia and Persia. The publication of the special issue, however, did not terminate the discussion; three other papers were subsequently published in the journal, the last in 1993. The discussion often came to be referred to as the ‘Feudalism Debate‘. A collection of concerned essays was published in New Delhi in 1999 under the title The Feudalism Debate.

FEUDALISM RECONSIDERED

While the debate critically examined the theoretical proposition of the universality of the concept of feudalism or otherwise – with each historian taking his own independent position – on the question of Indian historical evidence, R S Sharma, who was chiefly under attack, reconsidered some of his earlier positions and greatly refined his thhsis of Indian feudalism, even as he defended it vigorously and elegantly in a paper, ‘How Feudal was Indian Feudalism?‘ He had been criticised for looking at the rise of feudalism in India entirely as a consequence of state action in transferring land to the intermediaries; he modified it and expanded its scope to look at feudalism as an economic formation which evolved out of economic and social crises in society, signifying in the minds of the people the beginning of the Kaliyuga, rather than entirely as the consequence of state action. B N S Yadava also joined in with a detailed study of the notion of Kaliyuga in early medieval Indian literature and suggested that this notion had the characteristics of a crisis -the context for the transition of a society from one stage to another. All this considerably enriched the argument on behalf of Indian feudalism. R.S. Sharma was also able to trace several other instances of peasant resistance than the one he had unearthed in his 1965 book. This too has lent strength to the thesis. R S Sharma has lately turned his attention to the ideological and cultural aspects of the feudal society; in his latest collection of essays, published under the title Early Medieval Indian Society: A Study in Feudalisation in 2001 in New Delhi, he has revised several of his old arguments and included some new themes such as ‘The Feudal Mind’, where he explores such problems as the reflection of feudal hierarchies in art and architecture, the ideas of gratitude and loyalty as ideological props of feudal society, etc

This venture of extension into the cultural sphere has been undertaken by several other historians as well who abide by the notion of feudalism. In a collection of sixteen essays, The Feudal Order: State, Society and Ideology in Early Medieval India, 1987 and 2000, its editor D.N.Jha has taken care to include papers exploring the cultural and ideological dimensions of what he calls the feudal order, itself a comprehensive term. One of the major dimensions so explored is that of religion, especially popular religion or Bhakti, both in north and south India and the growth of India’s regional cultures and languages. Even as most scholars have seen the rise of the Bhakti cults as a popular protest against the domination of Brahmanical orthodoxy, the proponents of feudalism see these as buttresses of Brahmanical domination by virtue of the ideology of total surrender, subjection and loyalty to a deity. This surrender and loyalty could easily be transferred on to the feudal lord and master.

There have been certain differences of opinion among the historians of the Indian feudalism school too, D N Jha for example had found inconsistency between the locale of the evidence of the notion of Kaliyuga and site of the ‘crisis’ which the kaliyuga indicated: the evidence came from peninsular India, but the crisis was expected in Brahmanical north. B P Sahu too had cast doubt on the validity of the evidence of a kuliyuga as indicator of a crisis; instead, he had perceived it more as a redefinition of kingship and therefore a reassertion of Brahmanical ideology rather than a crisis within it.

Taking the cue from D.D. Kosambi’s formulations and inspired by Marc Bloch’s view that feudal social formations took place in non-European contexts, DN Jha followed the footsteps of R.S. Sharma, his mentor. He argued for a social formation marked by decentralised polity, preponderance of feudal lords (samantas), de-urbanisation, impoverishment of the peasantry and mounting influence of Brahmanical varna–jati norms at the cost of the lower social order, especially what is now called the a-varna group.

From the 1960s till the late 1990s, this was the most important historiographical debate among the specialists on early India, as Hermann Kulke and B.P. Sahu (History of Precolonial India: Issues and Debates, 2019) demonstrate. Afew things need to be noted here.

First, by arguing for a feudal formation in India, the thoroughbred Marxist historians – D.N. Jha included – moved away from Marx’s formulation of the Asiatic Mode of Production that perceived the pre-colonial Indian society as unchanging and immutable.

The proponents of Indian feudalism established the capacity of the Indian society to change and change outside dynastic shifts. This was the most significant impact of their studies and led to the coinage of a new period, the early medieval in Indian history. Ranging from roughly AD 400 to 1300, this period now figures as a phase of transitions from the ancient to the medieval.

The third point of note is their profuse use of inscriptional data, mainly gleaned from copper plates recording grants of revenue-free landed properties in favour of brahmanas and other religious grantees. These documents are descriptive sources, no less significant than the prescriptive Brahmanical sources in the Sruti-Smriti tradition. Raging debates ensued for and against feudal formations in India of the pre-1300 days.

A striking point is that major critiques to R.S. Sharma, D.N. Jha, B.N.S. Yadava and K.M. Shrimali came from several Marxist historians themselves, notably Harbans Mukhia. Using the same genre of inscriptional data, scholars like B.D. Chattopadhyaya, Noboru Karashima, Hermann Kulke and B.N. Mukherjee presented images to the contrary and portrayed the consolidation of the monarchical state-society, vibrant trade, new forms of urban growth and most importantly, the significance of socio-political formations at local levels. The search for centralisation and decentralisation of the state machinery was not given centrality in the counter-arguments to the proponents to Indian feudalism.

Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi